The United States Patent and Trademark Office has prepared interim guidance (2014 Interim Guidance on Patent Subject Matter Eligibility, called “Interim Eligibility Guidance”) for use by USPTO personnel in determining subject matter eligibility under 35 U.S.C. 101 in view of recent decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court (Supreme Court) such as Alice, Myriad, and Mayo.

The guidelines provide the following flowchart:

(Step 1) Is the claim to a process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter?

If so, proceed to Step 2A. If not, the claim is not eligible subject matter under 35 USC 101.

(Step 2A) [Part 1 Mayo test] Is the claim directed to a law of nature, a natural phenomenon, or an abstract idea (judicially recognized exceptions)?. If so, proceed to Step 2B. If not, the claim qualifies as eligible subject matter under 35 USC 101.

(Step 2B) [Part 2 Mayo test] Does the claim recite additional elements that amount to significantly more than the judicial exception? If so, the claim qualifies as eligible subject matter. If not, the claim is not eligible subject matter.

Two–part Analysis for Judicial Exceptions

A. Flowchart Step 2A (Part 1 Mayo Test) – Determine whether the claim is

directed to a law of nature, a natural phenomenon, or an abstract idea (judicial

exceptions).

A claim is directed to a judicial exception when a law of nature, a natural phenomenon,

or an abstract idea is recited (i.e., set forth or described) in the claim. Such a claim

requires closer scrutiny for eligibility because of the risk that it will “tie up” the excepted

subject matter and pre-empt others from using the law of nature, natural phenomenon, or

abstract idea. Courts tread carefully in scrutinizing such claims because at some level all

inventions embody, use, reflect, rest upon, or apply a law of nature, natural phenomenon,

or abstract idea. To properly interpret the claim, it is important to understand what the

applicant has invented and is seeking to patent.

For claims that may recite a judicial exception, but are directed to inventions that clearly

do not seek to tie up the judicial exception, see below regarding a streamlined

eligibility analysis.

It should be noted that there are no bright lines between the types of exceptions

because many of these concepts can fall under several exceptions. For example,

mathematical formulas are considered to be an exception as they express a scientific

truth, but have been labelled by the courts as both abstract ideas and laws of nature.

Likewise, “products of nature” are considered to be an exception because they tie up the

use of naturally occurring things, but have been labelled as both laws of nature and

natural phenomena. Thus, it is sufficient for this analysis to identify that the claimed

concept aligns with at least one judicial exception.

Laws of nature and natural phenomena, as identified by the courts, include naturally

occurring principles/substances and substances that do not have markedly different

characteristics compared to what occurs in nature. The types of concepts

courts have found to be laws of nature and natural phenomena are shown by these cases,

which are intended to be illustrative and not limiting:

• an isolated DNA (see the Myriad case);

• a correlation that is the consequence of how a certain compound is metabolized

by the body (Mayo);

• electromagnetism to transmit signals (Morse); and

• the chemical principle underlying the union between fatty elements and water

(Tilghman).

Abstract ideas have been identified by the courts by way of example, including

fundamental economic practices, certain methods of organizing human activities, an idea

‘of itself,’ and mathematical relationships/formulas. The types of concepts courts have

found to be abstract ideas are shown by these cases, which are intended to be illustrative

and not limiting:

• mitigating settlement risk (Alice);

• hedging (Bilski);

• creating a contractual relationship (buySAFE);

• using advertising as an exchange or currency (Ultramercial);

• processing information through a clearinghouse (Dealertrack);

• comparing new and stored information and using rules to identify options

(SmartGene);

• using categories to organize, store and transmit information (Cyberfone);

• organizing information through mathematical correlations (Digitech);

• managing a game of bingo (Planet Bingo);

• the Arrhenius equation for calculating the cure time of rubber (Diehr);

• a formula for updating alarm limits (Flook);

• a mathematical formula relating to standing wave phenomena (Mackay Radio); and

• a mathematical procedure for converting one form of numerical representation to

another (Benson)

Nature-based Products

a. Determine Whether The Markedly Different Characteristics Analysis Is

Needed To Evaluate a Nature-Based Product Limitation Recited in a Claim

Nature-based products, as used herein, include both eligible and ineligible products and

merely refer to the types of products subject to the markedly different characteristics

analysis used to identify “product of nature” exceptions. Courts have held that naturally

occurring products and some man-made products that are essentially no different from a

naturally occurring product are “products of nature” that fall under the laws of nature or

natural phenomena exception. To determine whether a claim that includes a nature-based

product limitation recites a “product of nature” exception, use the markedly different

characteristics analysis to evaluate the nature-based product limitation. A claim that recites a nature-based product limitation that does not

exhibit markedly different characteristics from its naturally occurring counterpart in its

natural state is directed to a “product of nature” exception (Step 2A: YES).

Care should be taken not to overly extend the markedly different characteristics analysis

to products that when viewed as a whole are not nature-based.

A nature-based product can be claimed by itself (e.g., “a Lactobacillus bacterium”) or as

one or more limitations of a claim (e.g., “a probiotic composition comprising a mixture of

Lactobacillus and milk in a container”). The markedly different characteristics analysis

should be applied only to the nature-based product limitations in the claim to determine

whether the nature-based products are “product of nature” exceptions. When the naturebased

product is produced by combining multiple components, the markedly different

characteristics analysis should be applied to the resultant nature-based combination,

rather than its component parts. In the example above, the mixture of Lactobacillus and

milk should be analyzed for markedly different characteristics, rather than the

Lactobacillus separately and the milk separately. The container would not be subject to

the markedly different characteristics analysis as it is not a nature-based product, but

would be evaluated in Step 2B if it is determined that the mixture of Lactobacillus and

milk does not have markedly different characteristics from any naturally occurring

counterpart and thus is a “product of nature” exception.

For a product-by-process claim, the analysis turns on whether the nature-based product in

the claim has markedly different characteristics from its naturally occurring counterpart.

(See MPEP 2113 for product-by-process claims.)

A process claim is not subject to the markedly different analysis for nature-based

products used in the process, except in the limited situation where a process claim is

drafted in such a way26 that there is no difference in substance from a product claim (e.g.,

“a method of providing an apple.”).

The markedly different characteristics analysis compares the nature-based product

limitation to its naturally occurring counterpart in its natural state. When there is no

naturally occurring counterpart to the nature-based product, the comparison should be

made to the closest naturally occurring counterpart. In the case of a nature-based

combination, the closest counterpart may be the individual nature-based components that

form the combination, i.e., the characteristics of the claimed nature-based combination

are compared to the characteristics of the components in their natural state.

Markedly different characteristics can be expressed as the product’s structure, function,

and/or other properties,28 and will be evaluated based on what is recited in the claim on a

case-by-case basis. As seen by the examples that are being released in conjunction with

this Interim Eligibility Guidance, even a small change can result in markedly different

characteristics from the product’s naturally occurring counterpart. In accordance with

this analysis, a product that is purified or isolated, for example, will be eligible when

there is a resultant change in characteristics sufficient to show a marked difference from

the product’s naturally occurring counterpart. If the claim recites a nature-based product

limitation that does not exhibit markedly different characteristics, the claim is directed to

a “product of nature” exception (a law of nature or naturally occurring phenomenon), and

the claim will require further analysis to determine eligibility based on whether additional

elements add significantly more to the exception.

Non-limiting examples of the types of characteristics considered by the courts when

determining whether there is a marked difference include:

• Biological or pharmacological functions or activities;

• Chemical and physical properties;

• Phenotype, including functional and structural characteristics; and

• Structure and form, whether chemical, genetic or physical.

If the claim includes a nature-based product that has markedly different characteristics,

the claim does not recite a “product of nature” exception and is eligible (Step 2A: NO)

unless the claim recites another exception (such as a law of nature or abstract idea, or a

different natural phenomenon). If the claim includes a product having no markedly

different characteristics from the product’s naturally occurring counterpart in its natural

state, the claim is directed to an exception (Step 2A: YES), and the eligibility analysis

must proceed to Step 2B to determine if any additional elements in the claim add

significantly more to the exception. For claims that are to a single nature-based product,

once a markedly different characteristic in that product is shown, no further analysis

would be necessary for eligibility because no “product of nature” exception is recited

(i.e., Step 2B is not necessary because the answer to Step 2A is NO). This is a change

from prior guidance because the inquiry as to whether the claim amounts to significantly

more than a “product of nature” exception is not relevant to claims that do not recite an

exception. Thus, a claim can be found eligible based solely on a showing that the naturebased

product in the claim has markedly different characteristics and thus is not a

“product of nature” exception, when no other exception is recited in the claim.

If a rejection under 35 U.S.C. 101 is ultimately made, the rejection should identify the

exception as it is recited (i.e., set forth or described) in the claim, and explain why it is an

exception providing reasons why the product does not have markedly different

characteristics from its naturally occurring counterpart in its natural state.

Flowchart Step 2B (Part 2 Mayo test) – Determine whether any element, or

combination of elements, in the claim is sufficient to ensure that the claim

amounts to significantly more than the judicial exception.

A claim directed to a judicial exception must be analyzed to determine whether the

elements of the claim, considered both individually and as an ordered combination, are

sufficient to ensure that the claim as a whole amounts to significantly more than the

exception itself – this has been termed a search for an “inventive concept.” To be

patent-eligible, a claim that is directed to a judicial exception must include additional

features to ensure that the claim describes a process or product that applies the exception

in a meaningful way, such that it is more than a drafting effort designed to monopolize

the exception. It is important to consider the claim as whole. Individual elements viewed

on their own may not appear to add significantly more to the claim, but when combined

may amount to significantly more than the exception. Every claim must be examined

individually, based on the particular elements recited therein, and should not be judged to

automatically stand or fall with similar claims in an application.

The Supreme Court has identified a number of considerations for determining whether a

claim with additional elements amounts to significantly more than the judicial exception

itself. The following are examples of these considerations, which are not intended to be

exclusive or limiting. Limitations that may be enough to qualify as “significantly more”

when recited in a claim with a judicial exception include:

• Improvements to another technology or technical field;

• Improvements to the functioning of the computer itself;

• Applying the judicial exception with, or by use of, a particular machine;

• Effecting a transformation or reduction of a particular article to a different state or

thing;

• Adding a specific limitation other than what is well-understood, routine and

conventional in the field, or adding unconventional steps that confine the claim to

a particular useful application; or

• Other meaningful limitations beyond generally linking the use of the judicial

exception to a particular technological environment.

Limitations that were found not to be enough to qualify as “significantly more” when

recited in a claim with a judicial exception include:

• Adding the words “apply it” (or an equivalent) with the judicial exception, or

mere instructions to implement an abstract idea on a computer;

• Simply appending well-understood, routine and conventional activities previously

known to the industry, specified at a high level of generality, to the judicial

exception, e.g., a claim to an abstract idea requiring no more than a generic

computer to perform generic computer functions that are well-understood, routine

and conventional activities previously known to the industry;

• Adding insignificant extrasolution activity to the judicial exception, e.g., mere

data gathering in conjunction with a law of nature or abstract idea; or

• Generally linking the use of the judicial exception to a particular technological

environment or field of use.

For a claim that is directed to a plurality of exceptions, conduct the eligibility analysis for

one of the exceptions. If the claim recites an element or combination of elements that

amount to significantly more than that exception, consider whether those additional

elements also amount to significantly more for the other claimed exception(s), which

ensures that the claim does not have a pre-emptive effect with respect to any of the

recited exceptions. Additional elements that satisfy Step 2B for one exception will likely

satisfy Step 2B for all exceptions in a claim. On the other hand, if the claim fails under

Step 2B for one exception, the claim is ineligible, and no further eligibility analysis is

needed.

The Interim Guidelines provide for a Streamlined Eligibility Analysis as follows.

For purposes of efficiency in examination, a streamlined eligibility analysis can be used

for a claim that may or may not recite a judicial exception but, when viewed as a whole,

clearly does not seek to tie up any judicial exception such that others cannot practice it.

Such claims do not need to proceed through the full analysis herein as their eligibility

will be self-evident. However, if there is doubt as to whether the applicant is effectively

seeking coverage for a judicial exception itself, the full analysis should be conducted to

determine whether the claim recites significantly more than the judicial exception.

For instance, a claim directed to a complex manufactured industrial product or process

that recites meaningful limitations along with a judicial exception may sufficiently limit

its practical application so that a full eligibility analysis is not needed. As an example, a

robotic arm assembly having a control system that operates using certain mathematical

relationships is clearly not an attempt to tie up use of the mathematical relationships and

would not require a full analysis to determine eligibility. Also, a claim that recites a

nature-based product, but clearly does not attempt to tie up the nature-based product,

does not require a markedly different characteristics analysis to identify a “product of

nature” exception. As an example, a claim directed to an artificial hip prosthesis coated

with a naturally occurring mineral is not an attempt to tie up the mineral. Similarly,

claimed products that merely include ancillary nature-based components, such as a claim that is directed to a cellphone with an electrical contact made of gold or a plastic chair

with wood trim, would not require analysis of the nature-based component to identify a

“product of nature” exception because such claims do not attempt to improperly tie up the

nature-based product.

Regardless of whether a rejection under 35 U.S.C. 101 is made, a complete examination

should be made for every claim under each of the other patentability requirements: 35 U.S.C. 102, 103, 112, and 101 (utility, inventorship and double patenting) and nonstatutory

double patenting.

The guidelines also provide sample analyses based upon earlier Supreme Court decisions.

The December 16, 2014 Interim Guidance can be found here:

https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2014/12/16/2014-29414/2014-interim-guidance-on-patent-subject-matter-eligibility

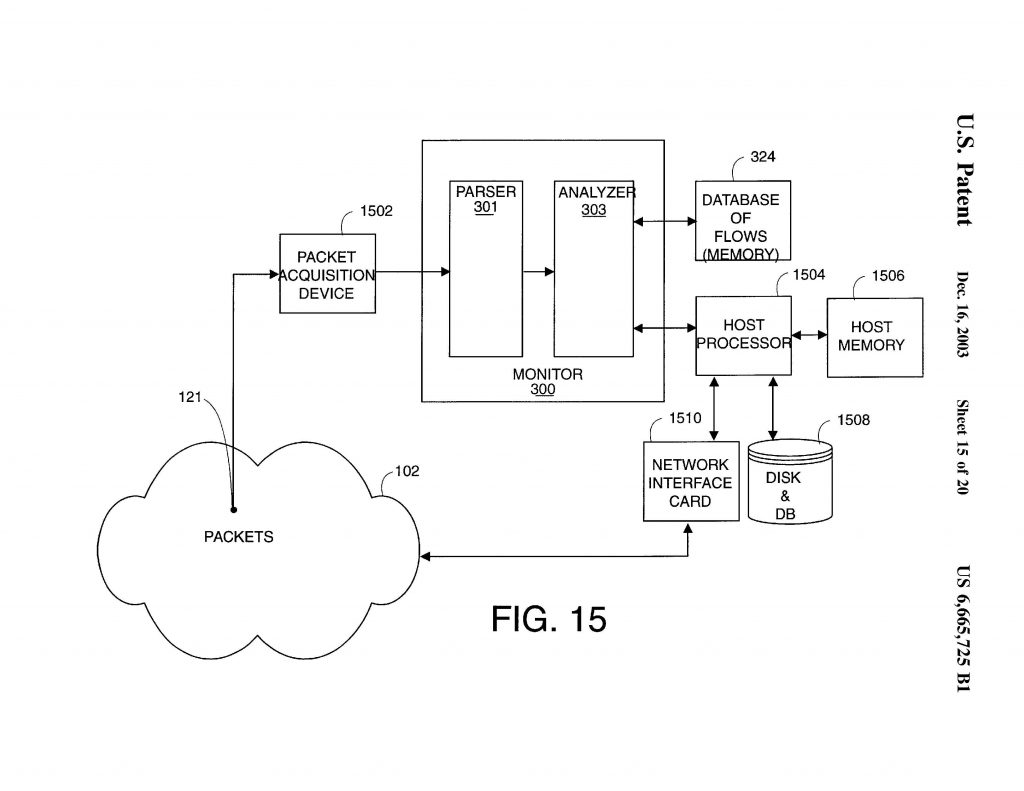

NetScout Systems appealed from a judgment of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas which held that NetScout willfully infringed various claims of U.S. Patent No. 6,665,725; 6,839,751; and 6,954,789 and held that the claims were valid under 35 U.S.C. §101.

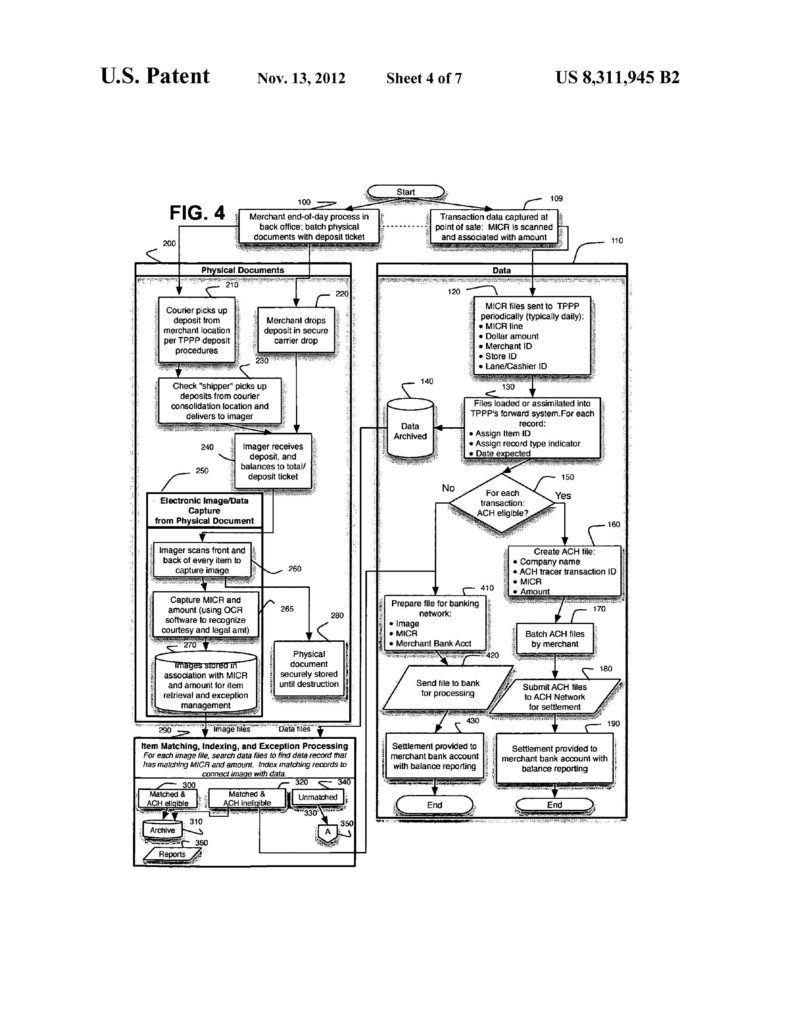

NetScout Systems appealed from a judgment of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas which held that NetScout willfully infringed various claims of U.S. Patent No. 6,665,725; 6,839,751; and 6,954,789 and held that the claims were valid under 35 U.S.C. §101. This decision involves U.S. Patent No. 8,311,945, assigned to Solutran, Inc.

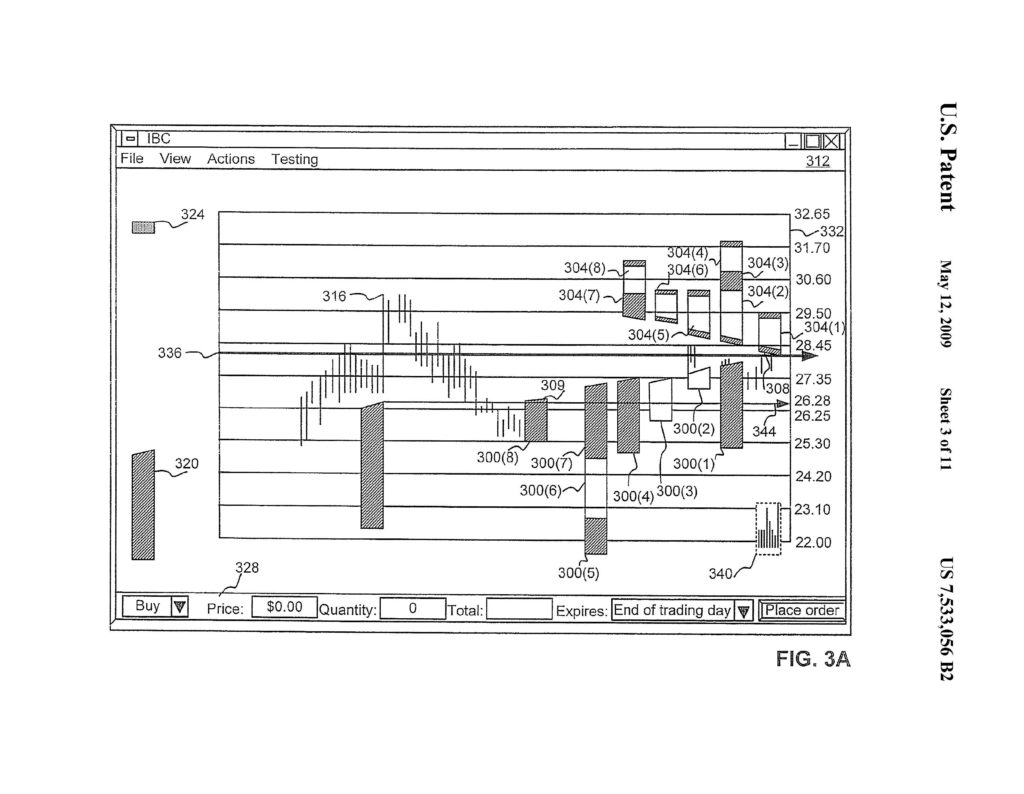

This decision involves U.S. Patent No. 8,311,945, assigned to Solutran, Inc. This decision involves Trading Technologies U.S. Patent Nos. 7,533,056; 7,212,999; and 7,904,374 covering graphical user interfaces for electronic trading.

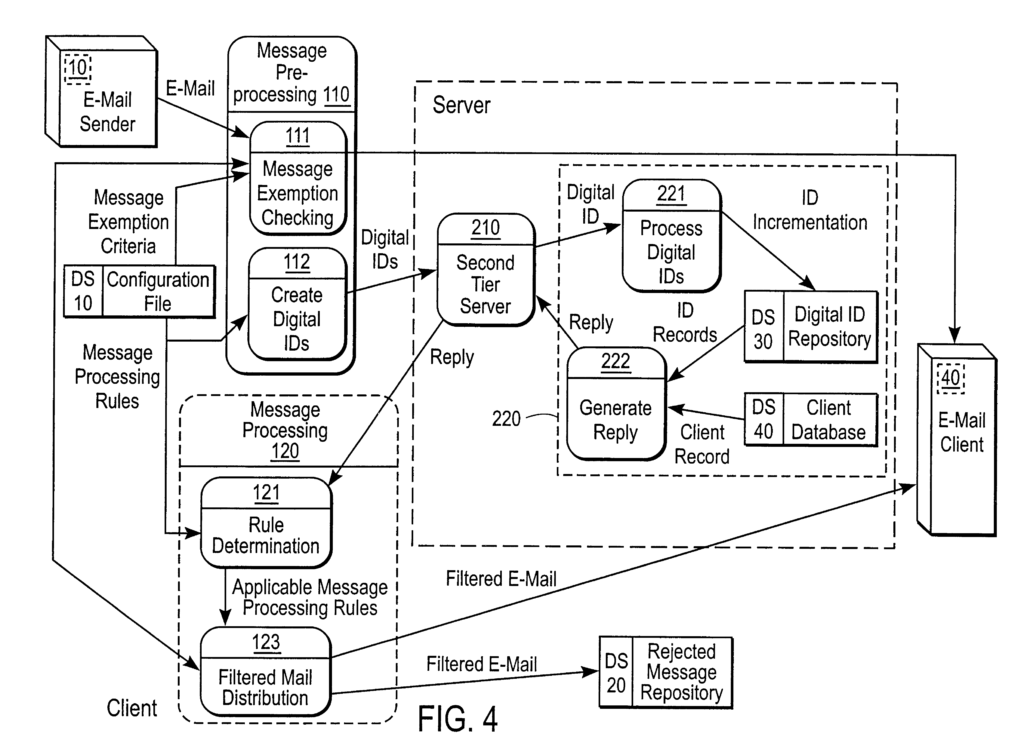

This decision involves Trading Technologies U.S. Patent Nos. 7,533,056; 7,212,999; and 7,904,374 covering graphical user interfaces for electronic trading. Intellectual Ventures I LLC (“IV”) sued Symantec Corp. and Trend Micro for infringement of various claims of U.S. Patent Nos. 6,460,050, 6,073,142, and 5,987,610. The district court held the asserted claims of the ’050 patent and the ’142 patent to be ineligible under § 101, and the asserted claim of the ’610 patent to be eligible. The Federal Circuit didn’t find any asserted claims to be patent-eligible.

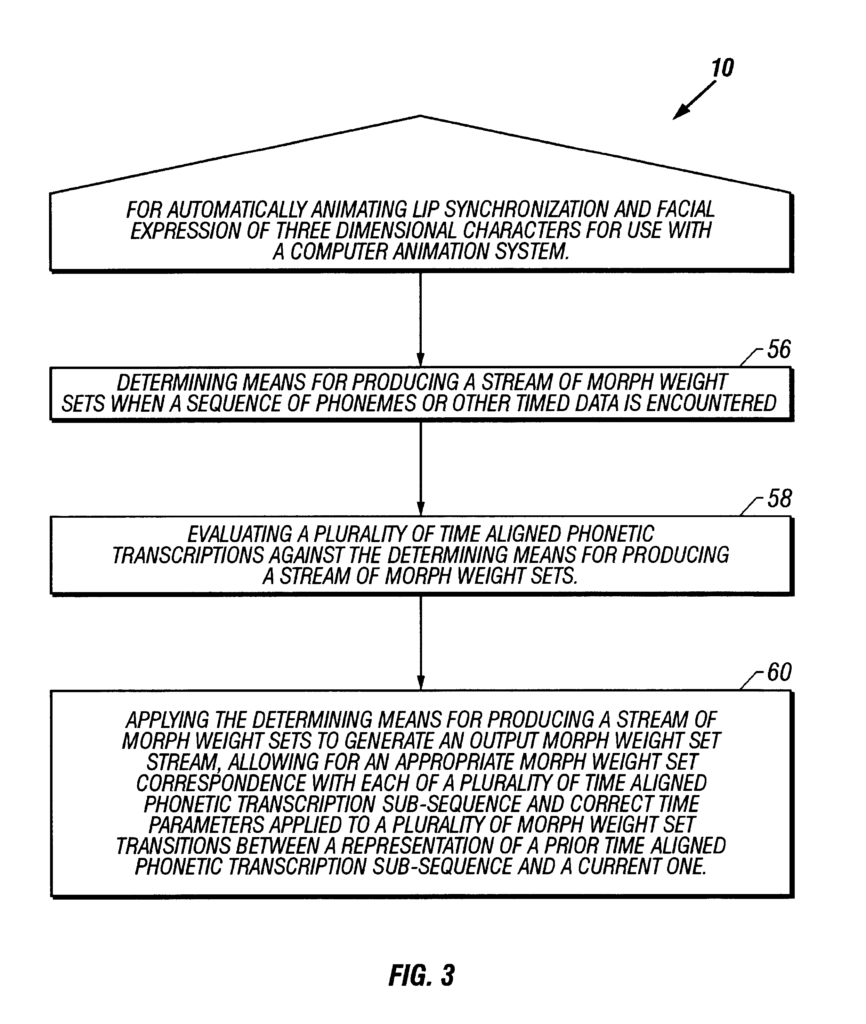

Intellectual Ventures I LLC (“IV”) sued Symantec Corp. and Trend Micro for infringement of various claims of U.S. Patent Nos. 6,460,050, 6,073,142, and 5,987,610. The district court held the asserted claims of the ’050 patent and the ’142 patent to be ineligible under § 101, and the asserted claim of the ’610 patent to be eligible. The Federal Circuit didn’t find any asserted claims to be patent-eligible. This was an appeal from a grant of judgment on the pleadings that the asserted claims of two software patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 6,307,576 (‘‘the ’576 patent’’) and 6,611,278 (‘‘the ’278 patent’’) were invalid.

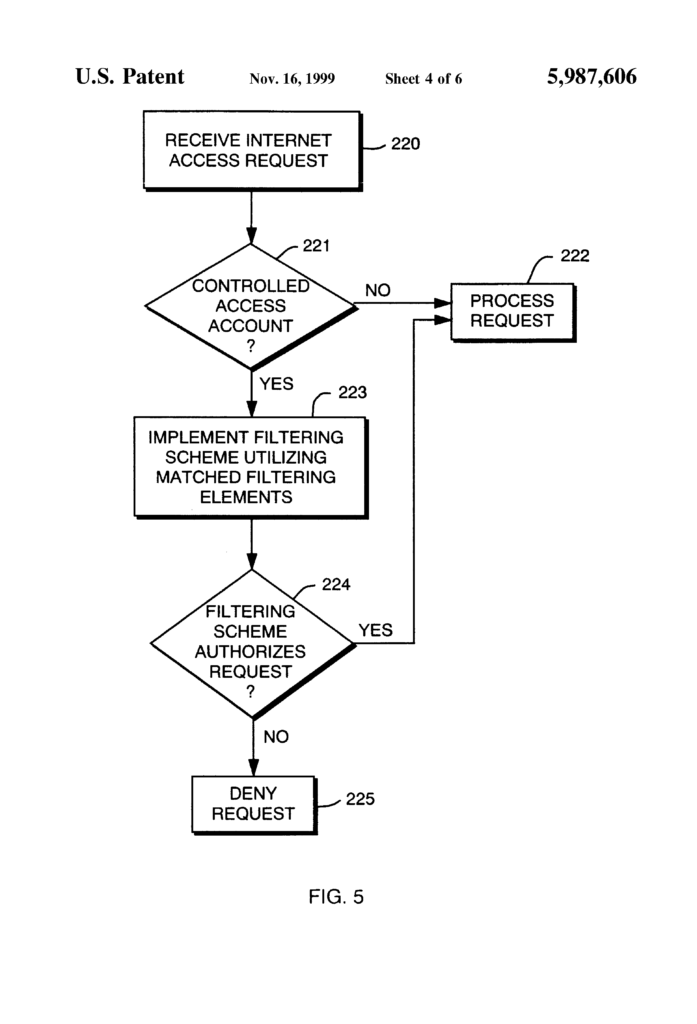

This was an appeal from a grant of judgment on the pleadings that the asserted claims of two software patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 6,307,576 (‘‘the ’576 patent’’) and 6,611,278 (‘‘the ’278 patent’’) were invalid. This was an appeal against a district court decision that the claims of U.S. Patent No. 5,987,606 are invalid as a matter of law under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

This was an appeal against a district court decision that the claims of U.S. Patent No. 5,987,606 are invalid as a matter of law under 35 U.S.C. § 101.