Though creating digital location histories is not patent eligible, a method of enhancing digital search results may be patent eligible.

Though creating digital location histories is not patent eligible, a method of enhancing digital search results may be patent eligible.

Mr. Sholem Weisner, an inventor of U.S. Patent Nos. 10,380,202, 10,642,910, 10,394,905 and 10,642,911 (along with Shmuel Nemanov)—sued Google LLC for patent infringement.

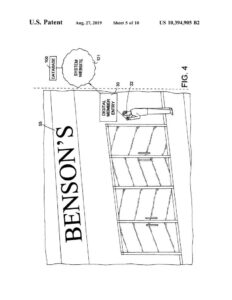

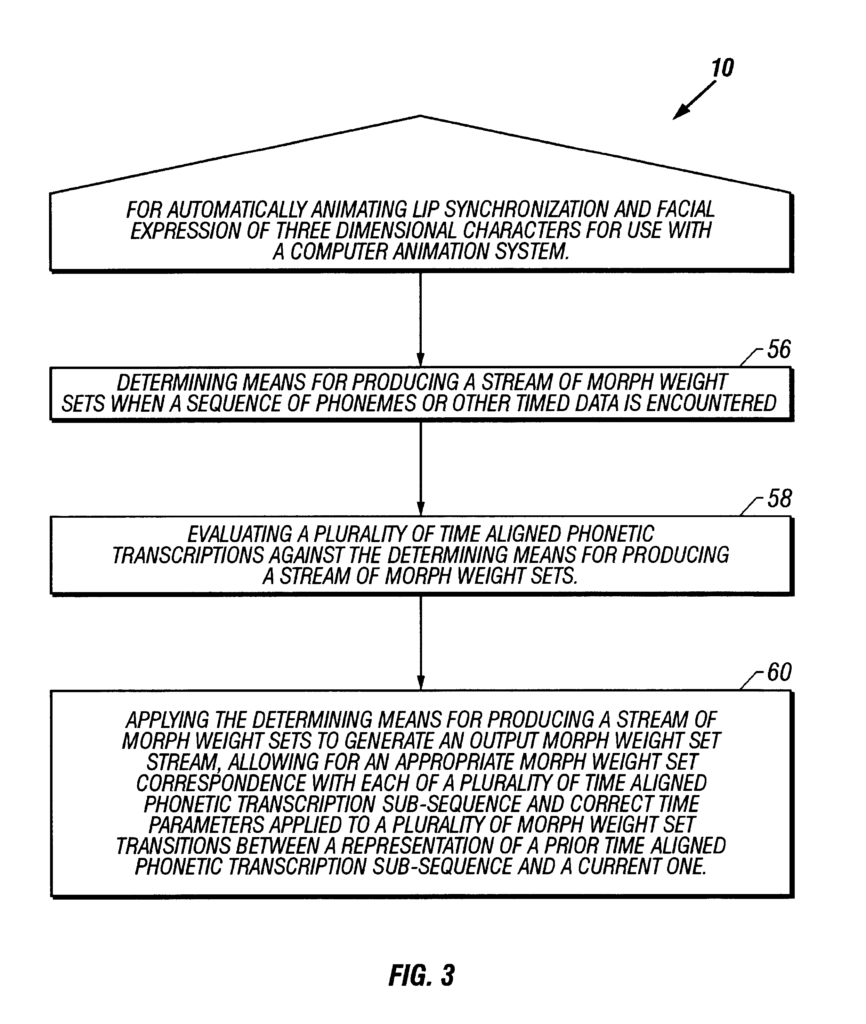

The four patents are related and share a common specification. The specification describes ways to digitally record a person’s physical activities and ways to use this information. Individuals and businesses can sign up for a system so that they can exchange information, for instance a URL or an electronic business card. Then, as individuals go about their day, they may encounter people or businesses that they want recorded in their “leg history,” which records the URLs or business cards along with the time and place of the encounters. The specification describes a “leg history” as the accumulation of a digital record of a person’s physical presence across time. Individuals record entries in their travel history either by accepting a proposal from another person/business (e.g., by pushing a button), or by unilaterally making an entry (e.g., by taking a snapshot with a digital camera and uploading it to their databank). These methods are illustrated in Figure 3 (showing a user accepting a proposed entry by Macy’s) and Figure 4 (showing a user unilaterally making an entry at “Benson’s” by taking a photograph): The specification also describes using this collected travel history data to enhance web searching results. For example, the specification describes a method for enhancing search results by using a useful person—someone that has visited a location in common with the searching person. In response to a person’s search, the system cross-references the digital histories of the searching person and the useful person to establish a common visit (e.g., “www.fourseasons.com” in and then gives priority to those search results that are found in the useful person’s travel history (e.g., “www.vegassteakhouse.com”).

Claim 1 of the ’202 patent recites recording physical location histories” of individual members that visit stationary vendor members in a member network. Claim 1 recites:

1. A method of creating and/or using physical location histories, comprising:

- maintaining a processing system that is connected to a telecommunications network and configured to provide an account to an individual member and to a stationary vendor member of a member network;

- providing an application that configures a handheld mobile communication device of each individual member of a member network to, upon instances of a physical encounter between the individual member and the stationary vendor member of a plurality of stationary vendor members of the member network at a physical premises of the stationary vendor member, a location of the physical encounter determined by a positioning system in communication with either the handheld mobile communication device or a communication device of the stationary vendor member, and upon acceptance by the handheld mobile communication device of the individual member of an automatic proposal from the stationary vendor member, transmit a URL of the stationary vendor member and a URL of the individual member to the processing system automatically, thereby generating a location history entry, in at least the account of the individual member, that includes (i) the URL of, and a location of, the stationary vendor member, (ii) a time and date of the physical encounter, and (iii) an identity or the account of the individual member and of the stationary vendor member,

- the URL of the individual member associated with the individual member before the physical encounter between the individual member

and the stationary vendor member; - the application maintaining a viewable physical encounter history on the handheld mobile communication device that includes URLs from multiple stationary vendor members and is searchable from the handheld mobile communication device (i) by URL of the individual member and of the stationary vendor member, (ii) by geographic location, and (iii) by time of the physical encounter,

- maintaining, using the processing system, a database of physical encounter histories of members of the member network whose accounts

received the location history entry that was generated during the physical encounters, the individual member’s account having data transfer privileges that allow the physical encounter history to be accumulated through transmission of location history entries from multiple handheld mobile communication devices of the individual member over time; and - wherein the physical encounter history of a particular individual member includes at least one visual timeline of physical encounters of the particular individual member.

Claim 1 of the ’910 patent is similar. It, too, describes accumulation of physical location histories.” It likewise recites generic features such as an “application,” “handheld mobile communication device,” “database,” etc. Id. The ’910 patent’s recited method, however, involves “capture by the particular individual member” that is processed “automatically.”

The representative claims of the remaining two patents have a different focus: using physical location histories to improve computerized search results. Claim 1 of the ’911 patent recites:

1. A computer-implemented method of enhancing digital search results for a business in a target geographic area using URLs of location histories, comprising:

- providing, by at least one processing system in communication with a positioning system, an

account to (i) an individual member and (ii) a stationary vendor member, of a member network, the account associated with a URL, the individual member’s account associated with a mobile communication device or multiple mobile communication devices, - maintaining a communication link between the mobile communication device and the at least one processing system or the positioning system such that the mobile communication device is configured to accumulate a location history on a database maintained by the at least one processing system from physical encounters by the individual member at multiple stationary vendor members upon the mobile communication device being set to enter instances of a physical encounter between the individual member carrying the mobile communication device and the stationary vendor member at a physical premises of the stationary vendor member, the positioning system determining a location of the individual member at the physical premises;

- for each individual member having a location history who sends a search query to a search engine of the at least one processing system, the search query targeting a geographic area:

(1) searching, by the search engine, the database for URLs of stationary vendor members in the location history, the location history also identifying time and geographic place of the physical encounters therein, and

(2) assigning a priority, by the at least one processing system, in a search result ranking based on an appearance of one of the stationary vendor member URLs in the location history of the individual member, wherein that one of the URLs is of a particular stationary vendor member located in the target geographic area.

Claim 1 of the ‘905 patent recites:

1. A method of combining enhanced computerized searching for a target business with use of humans as physical encounter links, comprising:

- maintaining a processing system connected to a telecommunications network;

- providing an application that allows a handheld mobile communication device of each individual member of a member network, the device in communication with a—positioning system, upon a physical encounter between the individual member and a stationary vendor member of a plurality of stationary vendor

members of the member network at a physical premises of the stationary vendor member, to

transmit key data of the stationary vendor member and of the individual member to the processing system automatically as a result of the physical encounter, a location of each individual member’s device determined by the positioning system, the key data being a URL or an identifier associated with the URL; - maintaining, using the processing system, a database of physical location histories of members of the member network whose key data was transmitted to the processing system during the physical encounters,

- determining, by the processing system, a physical location relationship recorded in the database between a searching person who is a member of the member network, a reference individual member of the member network and a first stationary vendor member of the plurality of stationary vendor members, upon the searching person making a search query on a search engine having access to the processing system; and

- responding to the search query by generating a computerized search result that increases a ranking of the first stationary vendor member based on the physical location relationship wherein the relationship is as follows:

(a) the reference individual member’s physical location history includes key data of the

first stationary vendor member; and

(b) the searching person’s physical location history and the reference individual member’s physical location history each include key data of a second stationary vendor member of the plurality of stationary vendor members, - wherein the searching person’s physical location relationship to the first stationary vendor

member is such that the searching person has a physical location relationship with the second stationary vendor member who has a physical location relationship with the reference individual member who has a physical location relationship with the first stationary vendor member.

Google moved to dismiss Mr. Weisner’s Complaints. Google argued that the asserted patent claims are ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101. Google also argued that Mr. Weisner had failed to meet the minimum threshold for plausibly pleading his claim of patent infringement.

If you have read any of the other posts in Malhotra Law Firm’s History of Software Patents, you will be well aware that the Supreme Court has set forth a two-step framework for analyzing patent eligibility in Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank Int’l, First, in Alice Step 1, the Federal Circuit is to determine whether the claims at issue are directed to patent-ineligible concepts such as laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas. If so, in Alice Step 2, the Federal Circuit is to examine the elements of each claim, considered both individually and as an ordered combination, for an “inventive concept” sufficient to transform the nature of the claim into a patent eligible application.

At step one of Alice, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the representative claims2 of these patents are directed to an abstract idea. The district court correctly determined that the patent claims are directed to collecting information on a user’s movements and location history and electronically recording that data.

As the district court correctly observed, humans have consistently kept records of a person’s location and travel in the form of travel logs, diaries, journals, and calendars, which compile information such as time and location. Automation or digitization of a conventional method of organizing human activity like the creation of a travel log on a computer does not bring the claims out of the realm of abstractness. The fact that the claims recite a number of generic elements—including a processing system, an application, and a handheld mobile communication device—does not shift their focus away from the core idea of creating a digital travel log.

Mr. Weisner argued that the claims are not abstract because they are directed to only capturing the travel history of “members.” According to Mr. Weisner, this improves the “integrity” of the data and avoids an “inundation of information making it useless.” According to the Federal Circuit, these purported technological advantages were nothing more than attorney argument, unlinked to the complaint or the patent claims or specification. Neither the specification nor the complaint addresses this purported technological improvement. Although the claims do recite a “member of the member network” and other “member” limitations, they do not limit the data collection to only members. Thus, the purported benefit of limiting data accumulation to members is not captured in the claims and, accordingly, does not shift the focus of the claims away from the abstract idea of creating a digital travel log.

Turning to step two, the Federal Circuit considered the elements of each claim both individually and as an ordered combination to determine whether the claims recite “something more” than the abstract idea to transform the nature of the claim into a patent-eligible application.

According to the Federal Circuit, the district court appropriately determined that the specification describes the components and features listed in the claims generically.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that these claims do not recite significantly more than the abstract idea of digitizing a travel log using conventional components. Mr. Weisner again argued that the claim limitations directed to “members” provide the something more to transform the claims into a patent-eligible invention. However, this argument is not linked to the claims.

Turning next to the ’905 and ’911 patents, the Federal Circuit determined that the challenged claims of these patents had not been shown to be ineligible at the Rule 12(b)(6) stage (motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim), where the court must accept all well-pleaded factual allegations as true and must construe all reasonable inferences in favor.

At step one, the district court erred by failing to separately analyze these patents. Although the specifications

in all four patents are the same, the claims of the ’905 and ’911 patents are not directed to the same subject matter as the ’202 and ’910 patents. Rather, at step one, the Federal Circuit concluded that the representative claims of the ’905 and ’911 patents are directed to creating and using travel histories to improve computerized search results.

Turning to step two of Alice, the Federal Circuit concluded that Mr. Weisner had plausibly alleged that the ’905 and ’911 patent claims recite a specific implementation of the abstract idea that purports to solve a problem unique to the Internet and that, accordingly, these claims should not have been held ineligible under step two at this stage.

Claim 1 of the ‘905 patent uses a “physical location relationship” with a third-party “reference individual” to increase the priority of search results. Claim 1 describes how the physical relationship is established—the system

searches the physical location histories of both a reference individual and the searching person to determine whether they have visited a common location (“second stationary vendor member”). The system then prioritizes search results that the reference individual has visited. According to the Federal Circuit, this is more than just the concept of improving a web search using location history—it is a specific implementation of that concept.

Try to disclose and claim improvements to computer operations. Solving a problem unique to the Internet may be sufficient. Try to disclose and recite detail in the claims if possible. This may go against your nature if you normally try to obtain the broadest claims possible. If you need help protecting your software, contact Malhotra Law Firm, PLLC.

Even patent applications covering mechanical inventions can be invalidated using the same

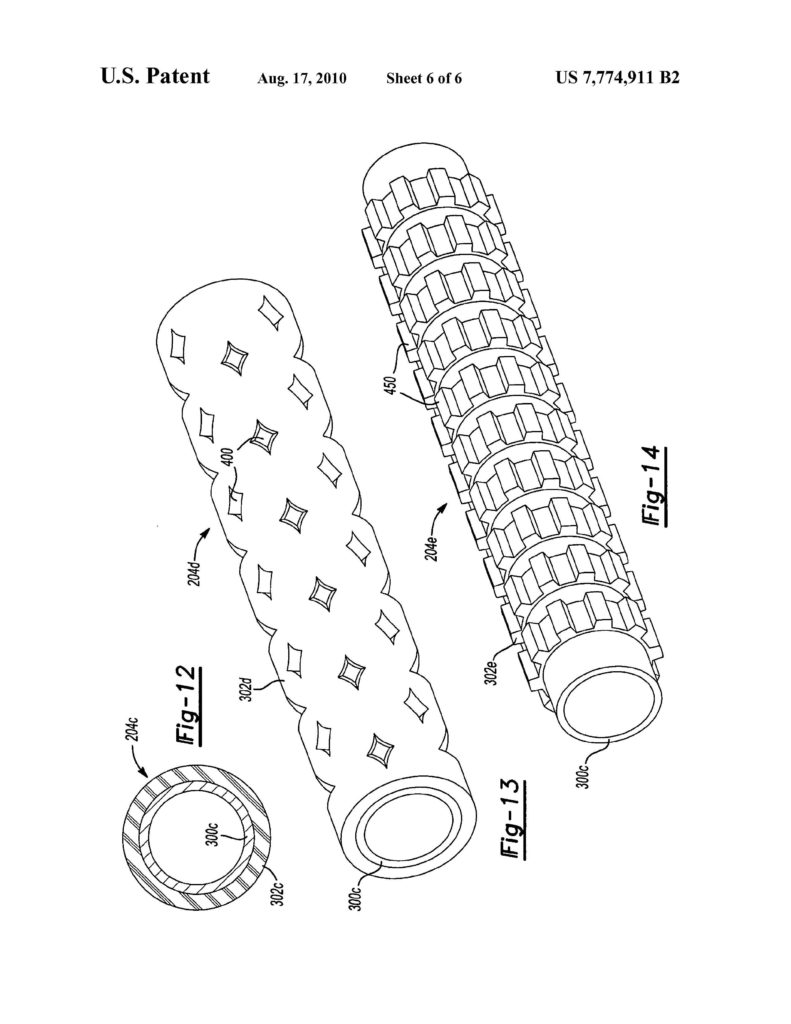

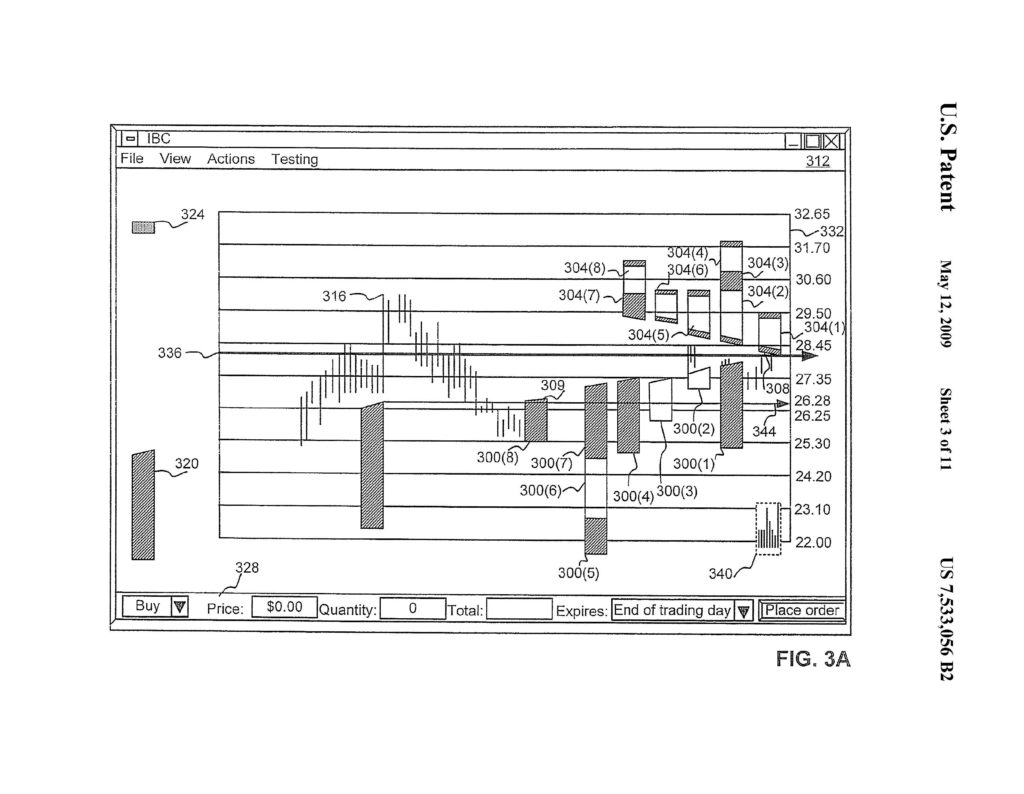

Even patent applications covering mechanical inventions can be invalidated using the same  This decision involves Trading Technologies U.S. Patent Nos. 7,533,056; 7,212,999; and 7,904,374 covering graphical user interfaces for electronic trading.

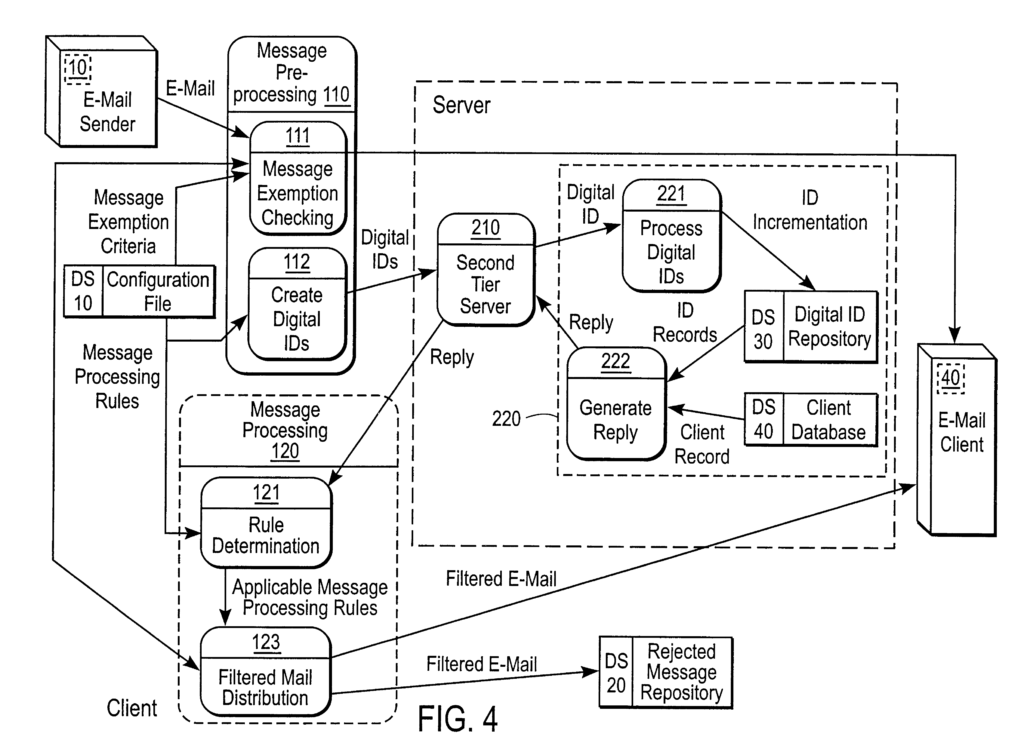

This decision involves Trading Technologies U.S. Patent Nos. 7,533,056; 7,212,999; and 7,904,374 covering graphical user interfaces for electronic trading. Intellectual Ventures I LLC (“IV”) sued Symantec Corp. and Trend Micro for infringement of various claims of U.S. Patent Nos. 6,460,050, 6,073,142, and 5,987,610. The district court held the asserted claims of the ’050 patent and the ’142 patent to be ineligible under § 101, and the asserted claim of the ’610 patent to be eligible. The Federal Circuit didn’t find any asserted claims to be patent-eligible.

Intellectual Ventures I LLC (“IV”) sued Symantec Corp. and Trend Micro for infringement of various claims of U.S. Patent Nos. 6,460,050, 6,073,142, and 5,987,610. The district court held the asserted claims of the ’050 patent and the ’142 patent to be ineligible under § 101, and the asserted claim of the ’610 patent to be eligible. The Federal Circuit didn’t find any asserted claims to be patent-eligible. This was an appeal from a grant of judgment on the pleadings that the asserted claims of two software patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 6,307,576 (‘‘the ’576 patent’’) and 6,611,278 (‘‘the ’278 patent’’) were invalid.

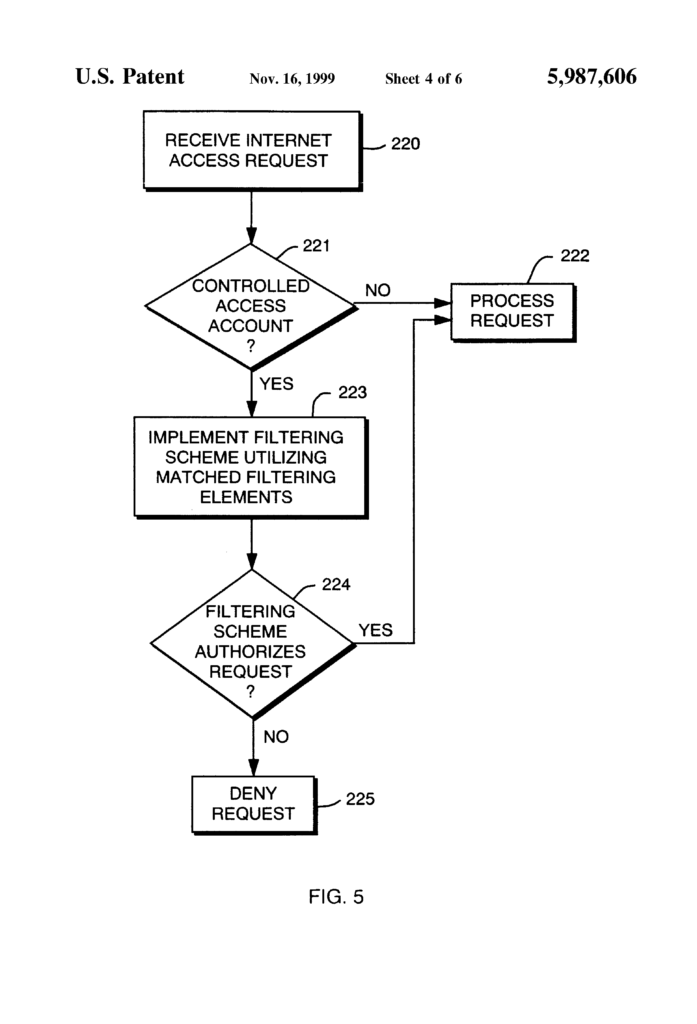

This was an appeal from a grant of judgment on the pleadings that the asserted claims of two software patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 6,307,576 (‘‘the ’576 patent’’) and 6,611,278 (‘‘the ’278 patent’’) were invalid. This was an appeal against a district court decision that the claims of U.S. Patent No. 5,987,606 are invalid as a matter of law under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

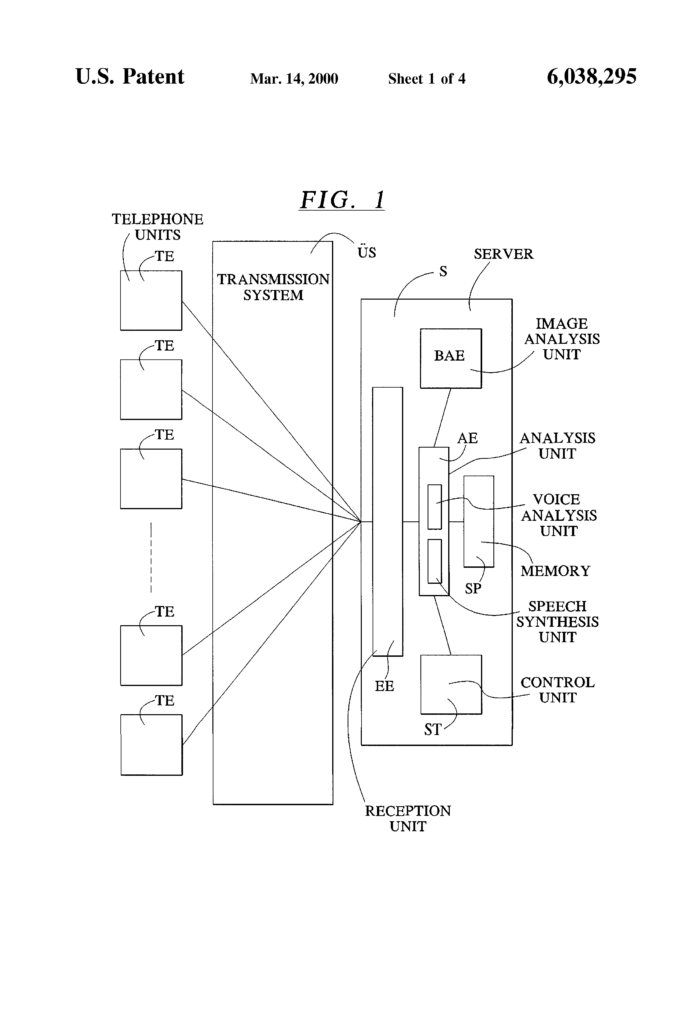

This was an appeal against a district court decision that the claims of U.S. Patent No. 5,987,606 are invalid as a matter of law under 35 U.S.C. § 101. TLI Communications hold U.S. Patent No. 6,038,295 relating to a method and system for taking, transmitting, and organizing digital images.

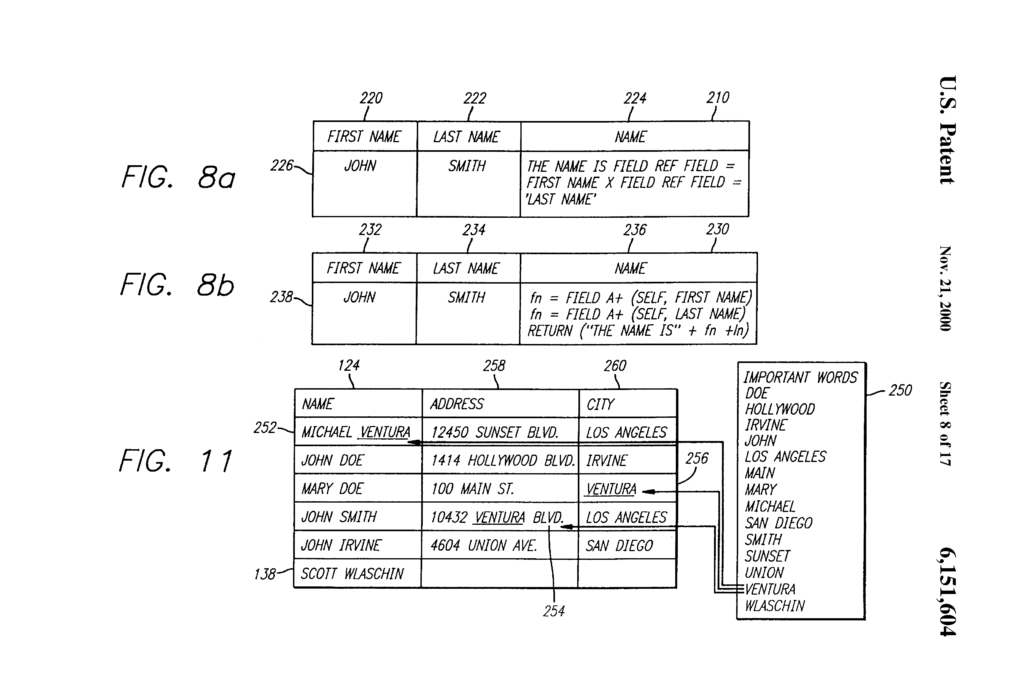

TLI Communications hold U.S. Patent No. 6,038,295 relating to a method and system for taking, transmitting, and organizing digital images. Enfish sued Microsoft for infringement of U.S. Patent 6,151,604 and U.S. Patent 6,163,775 related to a logical model for a computer database. A logical model is a model of data for a computer database explaining how the various elements of information are related to one another. A logical model generally results in the creation of particular tables of data, but it does not describe how the bits and bytes of those tables are arranged in physical memory devices. Contrary to conventional logical models, the patented logical model includes all data entities in a single table, with column definitions provided by rows in that same table. The patents describe this as a “self-referential” property of the database.

Enfish sued Microsoft for infringement of U.S. Patent 6,151,604 and U.S. Patent 6,163,775 related to a logical model for a computer database. A logical model is a model of data for a computer database explaining how the various elements of information are related to one another. A logical model generally results in the creation of particular tables of data, but it does not describe how the bits and bytes of those tables are arranged in physical memory devices. Contrary to conventional logical models, the patented logical model includes all data entities in a single table, with column definitions provided by rows in that same table. The patents describe this as a “self-referential” property of the database.