USC brought suit for infringement against Facebook, Inc. (now Meta Platforms, Inc.), asserting that its “News Feed” feature infringes claims 1–17 of U.S. Patent No. 8,645,300. The software patent relates to a search engine software method for predicting which webpages to recommend to a web visitor based on inferences of the visitor’s “intent.” The software patent states that website navigation can be enhanced “by recording a visitor’s intent and recording page rankings that indicate how well the pages of a website match the visitor’s intent.” The software patent further explains that visitor intent can be inferred from historical intent data, the Uniform Resource Locator, the user’s visits, and optional user intent confirmation. The lower court, the Western District of Texas, granted summary judgment that claims 1–17 are invalid.

USC brought suit for infringement against Facebook, Inc. (now Meta Platforms, Inc.), asserting that its “News Feed” feature infringes claims 1–17 of U.S. Patent No. 8,645,300. The software patent relates to a search engine software method for predicting which webpages to recommend to a web visitor based on inferences of the visitor’s “intent.” The software patent states that website navigation can be enhanced “by recording a visitor’s intent and recording page rankings that indicate how well the pages of a website match the visitor’s intent.” The software patent further explains that visitor intent can be inferred from historical intent data, the Uniform Resource Locator, the user’s visits, and optional user intent confirmation. The lower court, the Western District of Texas, granted summary judgment that claims 1–17 are invalid.

Claim 1 was deemed representative and recites:

1. A method for predicting an intent of a visitor to a webpage, the method comprising:

- receiving into an intent engine at least one input parameter from a web browser displaying the webpage;

- processing the at least one input parameter in the intent engine to determine at least

one inferred intent; - providing the at least one inferred intent to the web browser to cause the at least one

inferred intent to be displayed on the webpage; - prompting the visitor to confirm the visitor’s intent;

- receiving a confirmed intent into the intent engine;

- processing the confirmed intent in the intent engine to determine at least one recommended webpage that matches the confirmed intent, the at least one recommended webpage selected from a plurality of webpages within a defined namespace;

- causing the webpage in the web browser to display at least one link to the at least one

recommended webpage; - prompting the visitor to rank the webpage for the inferred intent;

receiving a rank from the web browser; and - storing a datapoint comprising an identity of the webpage, the inferred intent and the

received rank.

As is usual when evaluating software patents, the Federal Circuit applied the two-step framework set forth in Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 77–80 (2012), and further detailed in Alice v. CLS. At step one, they “determine whether the claims at issue are directed to one of those patent-ineligible concepts” such as an abstract idea. At step two, they “consider the elements of each claim both individually and as an ordered combination to determine whether the additional elements transform the nature of the claim into a patent-eligible application.”

At Alice step one, the district court found that the ’300 patent claims “are directed to the abstract idea of ‘collecting, analyzing and using intent data,’” drawing analogy to the

claims invalidated in Electric Power Group, LLC v. Alstom S.A., 830 F.3d 1350 (Fed. Cir. 2016). At Alice step two, the district court found that the patent claims do not “recite any elements, when considered individually or ‘as an ordered combination,’ [that] contain

anything ‘significantly more’ than the abstract idea itself.”

The district court did not accept USC’s position that the intent engine serves a role that is not conventional, generic, or well-known. The district court held that the intent engine “is a purely functional ‘black box’ implemented using standard cloud platforms from well-known vendors.” The district court described USC’s expert’s testimony as making a “conclusory assertion that the claims present a ‘unique and novel way of delivering webpages to consumers that was not previously demonstrated in the prior art,’” finding that this testimony was not “backed by any concrete facts from the specification or the prior art.” The district court concluded that the claims are unpatentable.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the idea of using computers to predict the intent of visitors is insufficient to render the idea non-abstract. The Federal Circuit analogized to Univ. of Fla. Rsch. Found., Inc. v. Gen. Elec. Co., 916 F.3d 1363, 1367 (Fed.

Cir. 2019) where it was held that a process of collecting, analyzing, and manipulating data on a computer “is a quintessential ‘do it on a computer’” claim and an ineligible abstract idea). The Federal Circuit stated that the district court correctly found that nothing recited in the patent claims, despite the references to web browsers and webpages, affects the functionality of the computer itself.

Turning to Alice step two, the Federal Circuit stated that district court correctly found that the claims do not contain “significantly more” to remove the claims from generality and abstraction. The district court also correctly observed that “‘web pages,’ ‘web browsers’ and ‘databases’ . . .were well known in the prior art,” and “[n]othing in the

claims, understood in light of the specification, requires anything other than off-the-shelf, conventional computer, network, and display technology for gathering, sending,

and presenting the desired information.” (quoting Electric Power, 830 F.3d at 1355).

The district court held that other claim elements, including the “intent tool,” “ranking tool,” and “widget,” also “do not provide any inventive concept because [they are] standard web browser functionalit[ies].” Although USC argued that “the intent ranking formula” in the patent specification provides sufficient substance for the operation of the “intent engine,” the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that the intent engine is only “a purely functional ‘black box,’” for the claims are not directed to the use of this formula nor do they cover the formula itself, and the specification states that skilled artisans would know

“many standard formulas” that would be effective.

Practice tips:

- If there is no novel hardware, try to find a reason why the software improves operation of the computer itself;

- Provide and claim details of how the software operates, not just a high level description of the desired result; and

- Don’t suggest or imply that your solution is easy or that alternatives could be easily designed.

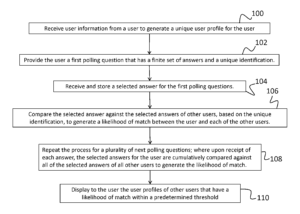

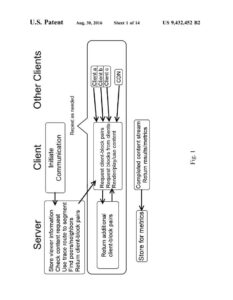

Trinity Info Media, LLC sued Covalent, Inc. for infringement of U.S. Patent Nos. 9,087,321 and 10,936,685 relating to methods and systems for connecting users based on their answers to polling questions. U.S. Patent No. 9,087,321 teaches that its claimed invention is “directed to a poll-based networking system that connects users based on similarities as determined through poll answering and provides real-time results to the users. The claimed invention of the ’685 patent is “directed to a poll-based networking and ecommerce system that connects users to other users, or products, goods and/or services based on similarities as determined through poll answering and provides real-time results to the users.

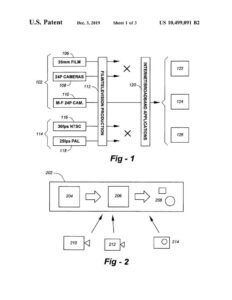

Trinity Info Media, LLC sued Covalent, Inc. for infringement of U.S. Patent Nos. 9,087,321 and 10,936,685 relating to methods and systems for connecting users based on their answers to polling questions. U.S. Patent No. 9,087,321 teaches that its claimed invention is “directed to a poll-based networking system that connects users based on similarities as determined through poll answering and provides real-time results to the users. The claimed invention of the ’685 patent is “directed to a poll-based networking and ecommerce system that connects users to other users, or products, goods and/or services based on similarities as determined through poll answering and provides real-time results to the users. A multi-format digital video product system capable of maintaining full-bandwidth resolution while providing professional quality editing and manipulation of images, which is capable of conserving bandwidth while preserving data is not patent-eligible.

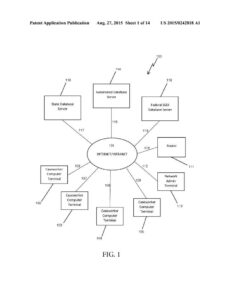

A multi-format digital video product system capable of maintaining full-bandwidth resolution while providing professional quality editing and manipulation of images, which is capable of conserving bandwidth while preserving data is not patent-eligible. The ITC took 35 U.S.C.

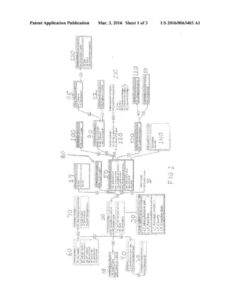

The ITC took 35 U.S.C.  Though creating digital location histories is not patent eligible, a method of enhancing digital search results may be patent eligible.

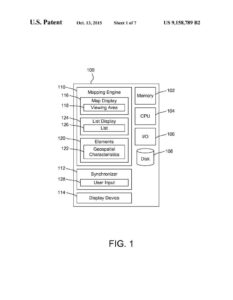

Though creating digital location histories is not patent eligible, a method of enhancing digital search results may be patent eligible. Functionally recited claims to organizing and displaying visual information are not patent-eligible.

Functionally recited claims to organizing and displaying visual information are not patent-eligible. At the pleadings stage, all that is required to survive a motion to dismiss based on Alice are plausible allegations in a complaint that the claims are patent-eligible.

At the pleadings stage, all that is required to survive a motion to dismiss based on Alice are plausible allegations in a complaint that the claims are patent-eligible. Mr. Smith’s argued that the first step in analyzing a claim must be to determine whether the claim is useful. And if it is useful, it is by law patent-eligible. The Federal Circuit disagreed.

Mr. Smith’s argued that the first step in analyzing a claim must be to determine whether the claim is useful. And if it is useful, it is by law patent-eligible. The Federal Circuit disagreed. A system and method for determining eligibility for Social Security Disability Insurance benefits by computer is directed to steps that can be performed in the human mind, or by a human using a pen and paper and is therefore a patent-ineligible abstract idea.

A system and method for determining eligibility for Social Security Disability Insurance benefits by computer is directed to steps that can be performed in the human mind, or by a human using a pen and paper and is therefore a patent-ineligible abstract idea.