American Axle & Manufacturing Inc. v. Neapco Holdings, FEDERAL CIRCUIT 2019 (LAWS OF NATURE)

Even patent applications covering mechanical inventions can be invalidated using the same Alice Corp. v CLS case law used to invalidate software patents.

Even patent applications covering mechanical inventions can be invalidated using the same Alice Corp. v CLS case law used to invalidate software patents.

American Axle & Manufacturing, Inc. sued Neapco alleging infringement of U.S. Patent No. 7,774,911.

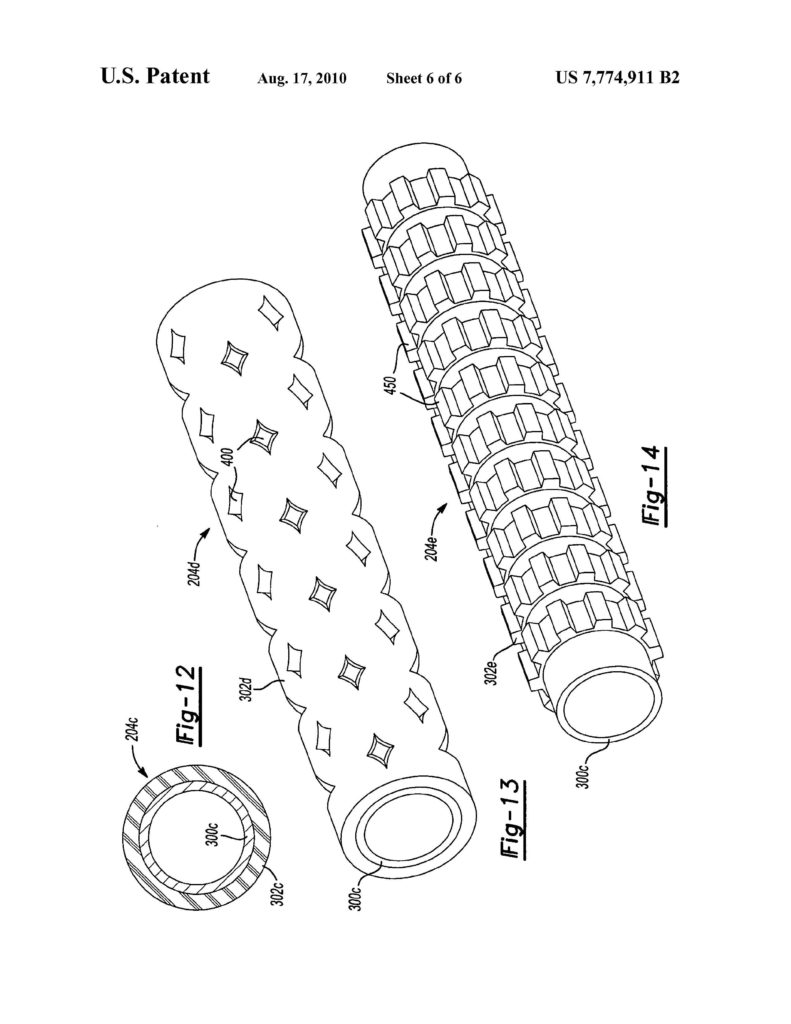

The patent generally relates to a method for manufacturing driveline propeller shafts with liners that are designed to attenuate vibrations transmitted through a shaft assembly.

Bending mode vibration is a phenomenon wherein energy is transmitted longitudinally along the shaft and causes the shaft to bend at one or more locations. Torsion mode vibration is a phenomenon wherein energy is transmitted tangentially through the shaft and causes the shaft to twist. Shell mode vibration is a phenomenon wherein as standing wave is transmitted circumferentially about the shaft and causes the cross-section of the shaft to deflect or bend along one or more axes. These vibration modes correspond to different frequencies.

Claims 1 and 22 are representative and recite:

1. A method for manufacturing a shaft assembly of a driveline system, the driveline system further including a first driveline component and a second driveline component, the shaft assembly being adapted to transmit torque between the first driveline component and the second driveline component, the method comprising:

- providing a hollow shaft member;

- tuning at least one liner to attenuate at least two types of vibration transmitted through the shaft member; and

- positioning the at least one liner within the shaft member such that the at least one liner is configured to damp shell mode vibrations in the shaft member by an amount that is greater than or equal to about 2%, and the at least one liner is also configured to damp bending mode vibrations in the shaft member, the at least one liner being tuned to within about ±20% of a bending mode natural frequency of the shaft assembly as installed in the driveline system.

22. A method for manufacturing a shaft assembly of a driveline system, the driveline system further including a first driveline component and a second driveline component, the shaft assembly being adapted to transmit torque between the first driveline component and the second driveline component, the method comprising:

- providing a hollow shaft member;

- tuning a mass and a stiffness of at least one liner, and

- inserting the at least one liner into the shaft member;

- wherein the at least one liner is a tuned resistive absorber for attenuating shell mode vibrations and wherein the at least one liner is a tuned reactive absorber for attenuating bending mode vibrations.

The district court construed the term tuning to mean “controlling the mass and stiffness of at least one liner to configure the liner to match the relevant frequency or frequencies.” Neither party contested this construction.

According to the patent’s specification, prior art liners, weights, and dampers that were designed to individually attenuate each of the three propshaft vibration modes—bending, shell, and torsion—already existed. But these prior art damping methods were assertedly not suitable for attenuating two vibration modes simultaneously.

The district court concluded that the Asserted Claims as a whole are directed to laws of nature: Hooke’s law and friction damping.

The Federal Circuit’s analysis of 35 U.S.C. § 101 follows the Supreme Court’s two-step test established in Mayo and Alice Corp. Pty. Ltd. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208 (2014). At step one of the Mayo/Alice test, we ask whether the claims are directed to a law of nature, natural phenomenon, or abstract idea. Alice, 573 U.S. at 217 (citing Mayo, 566 U.S. at 77). If the claims are so directed, the Federal Circuit then asks whether the claims embody some “inventive concept”—i.e., whether the claims contain “an element or combination of elements that is ‘sufficient to ensure that the patent in practice amounts to significantly more than a patent upon the ineligible concept itself.’”

AAM agreed that the selection of frequencies for the liners to damp the vibrations of the propshaft at least in part involves an application of Hooke’s law.Hooke’s law is a natural law that mathematically relates the mass and/or stiffness of an object to the frequency with which that object oscillates (vibrates). Here, both parties’ witnesses agreed that Hooke’s law undergirds the design of a liner so that it exhibits a desired damping frequency pursuant to the claimed invention. Neapco’s expert, Dr. Becker, stated that the tuning limitations claim “nothing more than Hooke’s law . . . [and/or] the law of nature / natural phenomenon for friction damping.”

AAM argued that the claims are not merely directed to Hooke’s law. AAM pointed to testimony suggesting that tuning a liner such that it attenuates two different vibration modes is a process that involves more than simple application of Hooke’s law.

The problem with AAM’s argument was that the solution to these desired results is not claimed in the patent. The Federal Circuit has repeatedly held that features that are not claimed are irrelevant as to step 1 or step 2 of the Mayo/Alice analysis.

This distinction between results and means is fundamental to the step 1 eligibility analysis, including in law-of-nature cases, not just abstract-idea cases.

The Federal Circuit stated that as to Mayo/Alice step 2, nothing in the claims qualifies as an “inventive concept” to transform the claims into patent eligible matter.

The Federal Circuit concluded that Claims 1 and 22 are not patent eligible.

As a patent drafting tip, claims of both software patents and mechanical patents should be drafted so as to include detail of how a problem is solved. Claims should not just be directed to laws of nature, but as to how the solution is achieved. In a software patent application, describe and claim some details of what’s under the hood (the algorithm) in a claim, not just the result. Inventors: give your patent attorney lots of details including flowcharts, in addition to screen shots. There is a common misconception that providing details in the specification means that the resulting patent will be too narrow. That is not true. The protection provided by a patent is determined by the claims, not the specification. A detailed specification does not necessarily mean narrow claims–instead, details in the specification provide the possibility of saving a patent application that is rejected as being patent-ineligible under Alice. Provide access to your programmers and require that the programmers cooperate with the patent attorney.