This decision involves U.S. Patent No. 8,311,945, assigned to Solutran, Inc.

This decision involves U.S. Patent No. 8,311,945, assigned to Solutran, Inc.

The patent explains that in the past, the payee would transport the check to his or her own bank to be read and processed, then the payee’s bank would transport the check to the payor’s bank,where it also would be read and processed. At this point, the payor’s bank would debit the payor’s account and transfer the money to the payee’s bank, which would credit the payee’s account.

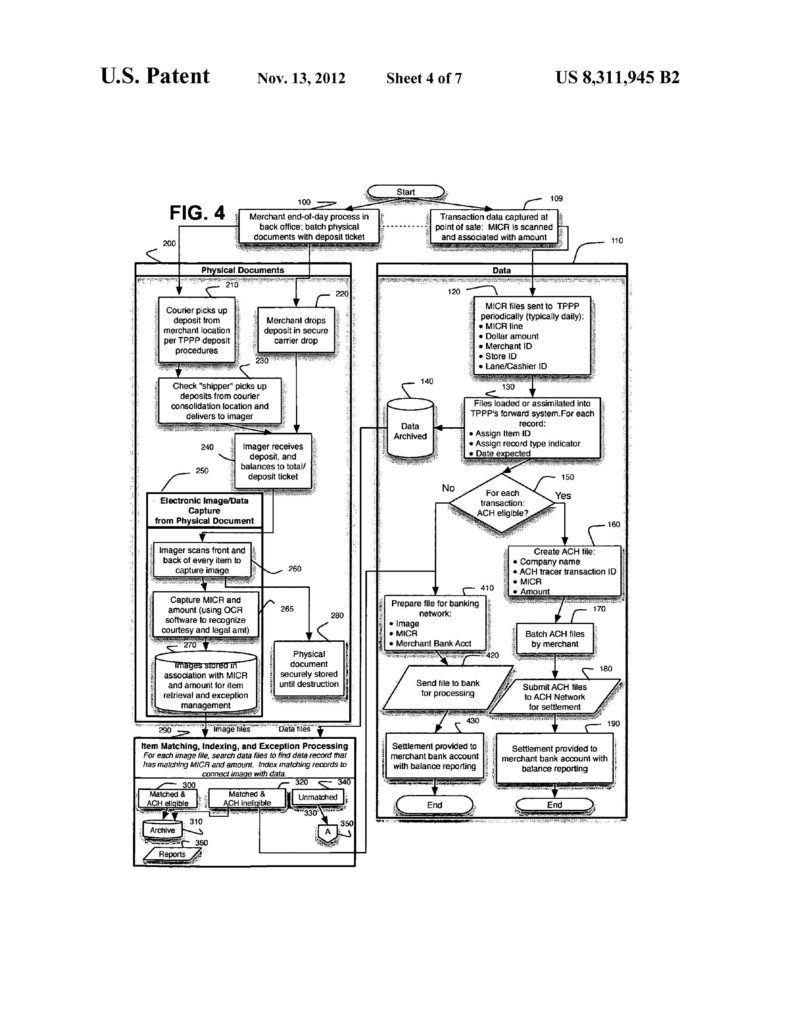

The digital age ushered in a faster approach to processing checks, where the transaction information—e.g., amount of the transaction, routing and account number—on the check is turned into a digital file at the merchant’s point of sale (POS) terminal.

The digital check information is sent electronically over the Internet or other network, and the funds are then transferred electronically from one account to another. By converting the check information into digital form, it no longer was always necessary to physically move the paper check from one entity to another to debit or credit the accounts. But retaining the checks was still useful for, among other things, verifying accuracy of the transaction data entered into the digital file.The patent also discloses a method proposed by the National Automated Clearing House Association (NACHA) for “back office conversion” where merchants scan their checks in a back office, typically at the end of the day, “instead of at the purchase terminal,” A scanner captures an image of the check, and MICR data from the check is stored with the image. An image file containing this information can be transferred to a bank or third-party payment processor.

The patent describes its invention as a system and method of electronically processing checks in which (1) data from the checks is captured at the point of purchase, (2) this data is used to promptly process a deposit to the merchant’s account, (3) the paper checks are moved elsewhere “for scanning and image capture,” and (4) “the image of the check is matched up to the data file.” The proffered benefits include “improved funds availability”for merchants and allegedly “relieving merchants] of the task, cost, and risk of scanning and destroying the paper checks themselves, relying instead on a secure, high-volume scanning operation to obtain digital images of the checks.” Solutran explains that its method allows merchants to get their accounts credited sooner, without having to wait for the check scanning step.

Claim 1 is representative and recites:

1. A method for processing paper checks, comprising:

- a) electronically receiving a data file containing data captured at a merchant’s point of purchase, said data including an amount of a transaction associated with MICR information for each paper check, and said data file not including images of said checks;

- b) after step a), crediting an account for the merchant;

- c) after step b), receiving said paper checks and scanning said checks with a digital image scanner thereby creating digital images of said checks and, for each said check, associating said digital image with said check’s MICR information; and

- d) comparing by a computer said digital images, with said data in the data file to find matches.

The (lower) district court concluded that the claims were not directed to an abstract idea and the patent was therefore patent-eligible. The district court found a previous covered business method (CBM) review of the patent by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (Board) persuasive in reaching its determination. The Board issued a decision denying a petition as to a §101 challenge, concluding that claim 1 of the patent was not directed to an abstract idea. The Board reasoned that “the basic, core concept of independent claim 1 is a method of processing paper checks, which is more akin to a physical process than an abstract idea.”

To determine whether claimed subject matter is patent-eligible, the Federal Circuit applied the two-step framework explained in Alice v CLS. First, the Federal Circuit is to “determine whether the claims at issue are directed to a patent-ineligible concept” such as an abstract idea. Second, if so, the Federal Circuit is to “examine the elements of the claim to determine whether it contains an ‘inventive concept’ sufficient to ‘transform’ the claimed abstract idea into a patent-eligible application.” At each step, the claims are considered as a whole.

With regard to Step One, the Federal Circuit agreed with U.S. Bank that the claims of the patent are directed to an abstract idea. The Federal Circuit concluded that the claims are directed to the abstract idea of crediting a merchant’s account as early as possible while electronically processing a check. The Federal Circuit noted that they had previously ruled that certain transaction claims performed in a particular order or sequence are directed to abstract ideas in Ultramercial, Inc. v. Hulu, LLC. In Ultramercial, the claims at issue were drawn to a method for distribution of copyrighted content over the Internet including the steps of receiving media from a content provider, selecting an ad, offering the media to the consumer in exchange for watching the ad, displaying the ad, then allowing the consumer to access the media. The Federal Circuit in Ultramercial determined that the ordered combination of steps recited “an abstraction—an idea, having no particular concrete or tangible form.” Id.at 715. We defined the abstract idea as “showing an advertisement be-fore delivering free content. Because the innovative aspect of the claimed invention in Ultramercial was an entrepreneurial rather than a technological one, the Federal Circuit deemed that invention patent-ineligible.

The Federal Circuit stated that, aside from the timing of the account crediting step, the ’945 patent claims recite elements similar to those in Content Extraction & Transmission LLC v. Wells Fargo Bank, NationalAss’n. There, they held that a method of extracting and then processing information from hard copy documents, including paper checks, was drawn to the abstract idea of collecting data, recognizing certain data within the collected data set, and storing that recognized data in a memory. In Content Extraction, the Federal Circuit explained that the concept of data collection, recognition, and storage is undisputedly well-known; indeed, humans have always performed these functions. Here, too, the claims recite basic steps of electronic check processing. In its background, the ’945 patent explains that “there has been an industry transition to the electronic processing of checks, including the recordation of the data… presented by the check into a digital format which can then be transferred electronically.” It had become standard for the merchant to capture the check’s transaction amount and MICR data at the point of purchase. Further, the patent’s background explains that verifying the accuracy of the transaction information stored in the digital file against the check was already common.

The Federal Circuit then analogized to other prior decisions. Crediting a merchant’s account as early as possible while electronically processing a check is a concept similar to those determined to be abstract by the Supreme Court in Bilski v. Kappos, and Alice itself. In Bilski, the Supreme Court determined that claims directed to “the basic concept of hedging, or protecting against risk” recited “a fundamental economic practice long prevalent in our system of commerce and taught in any introductory finance class” and therefore “an unpatentable abstract idea.” In Alice, the Supreme Court deemed “a method of exchanging financial obligations between two parties using a third-party intermediary to mitigate settlement risk” to be an abstract idea. The desire to credit a merchant’s account as soon as possible is an equally long-standing commercial practice. Solutran argued that the claims “as a whole” are not directed to an abstract idea. The ’945 patent articulates two benefits of its invention: (1) “improved funds availability” because the merchant’s account is credited before the check is scanned or verified; and (2) relieving merchants of the task, cost, and risk of scanning and destroying paper checks by out-sourcing those tasks. The only advance recited in the asserted claims is thus crediting the merchant’s account before the paper check is scanned. The Federal Circuit concluded that this is an abstract idea.

This is not a situation where the claims “are directed to a specific improvement to the way computers operate”as in cases such as Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp. Enfish is an example of a software patent that was held to be patent-eligible. Patent applicants considering filing a new patent application should always ask themselves whether their invention can be framed in terms of somehow improving operation of the computer.

The physicality of the paper checks being processed and transported is not by itself enough to exempt the claims from being directed to an abstract idea. As the Federal Circuit explained in In re Marco Guldenaar Holding B.V., 911 F.3d 1157, 1161 (Fed. Cir. 2018), “the abstract idea exception does not turn solely on whether the claimed invention comprises physical versus mental steps.” In fact, “[t]he claimed methods in Bilski and Alice also recited actions that occurred in the physical world.”

Similarly, the Federal Circuit has determined that a method for voting that involved steps of printing and handling physical election ballots, Voter Verified, Inc. v. Election Sys. & Software LLC, 887 F.3d 1376 (Fed. Cir. 2018), and a method of using a physical bankcard, Smart Sys. Innova-tions, LLC v. Chi.Transit Auth., 873 F.3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2017), were abstract ideas. And the Supreme Court has concluded that diagnostic methods that involve physical administration steps are directed to a natural law. Mayo, 566 U.S. at 92. The physical nature of processing paper checks in this case does not require a different result, where the claims simply recite conventional actions in a generic way (e.g., capture data for a file, scan check, move check to a second location, such as a back room) and do not purport to improve any underlying technology.

The district court’s and Solutran’s reliance on the paper checks being processed in two“different location[s]”via two paths as preventing the claims from being directed to an abstract idea is also misplaced. The claims on their face are broad enough to allow the transaction data to be captured at the merchant’s point of purchase and the checks to be scanned and compared in the merchant’s back office. The location of the scanning and comparison—whether it occurs down the hallway, down the street, or across the city—does not detract from the conclusion that these claims are, at bottom, directed to getting the merchant’s account credited from a customer’s purchase as soon as possible, which is an abstract idea.

With regard to Step Two of the Alice test, the Federal Circuit disagreed with the district court that the patent claims “contain a sufficiently transformative inventive concept so as to be patent eligible.” Even when viewed as a whole, these claims “do not, for example, purport to improve the functioning of the computer itself” or “effect an improvement in any other technology or technical field.” (see Alice v CLS). To the contrary, as the claims in Ultramercial did, the claims of the ’945 patent “simply instruct the practitioner to implement the abstract idea with routine, conventional activity.” As was noted above, the background of the ’945 patent describes each individual step in claim 1 as being conventional. Reordering the steps so that account crediting occurs before check scanning (as opposed to the other way around) represents the abstract idea in the claim, making it insufficient to constitute an inventive concept. Any remaining elements in the claims, including use of a scanner and computer and “routine data-gathering steps” (i.e.,receipt of the data file),have been deemed insufficient by the Federal Circuit in the past to constitute an inventive concept.

To the extent Solutran argues that these claims are patent-eligible because they are allegedly novel and non-obvious, the Federal Circuit has previously explained that merely reciting an abstract idea by itself in a claim—even if the idea is novel and non-obvious—is not enough to save it from ineligibility. See, e.g., Synopsys, Inc. v. Mentor Graphics Corp., 839 F.3d 1138, 1151 (Fed. Cir. 2016)

Solutran also argued that its claims pass the machine-or-transformation test—i.e., “transformation and reduction of an article ‘to a different state or thing.’” While the Supreme Court has explained that the machine-or-trans-formation test can provide a “useful clue” in the second step of Alice, passing the test alone is insufficient to overcome Solutran’s failings under step two. Merely using a general-purpose computer and scanner to perform conventional activities in the way they always have, as the claims do here, does not amount to an inventive concept. Because the claims of the ’945 patent recite the abstract idea of using data from a check to credit a merchant’s account before scanning the check, and because the claims do not contain an inventive concept sufficient to transform this abstract idea into a patent-eligible application, the claims were held to not be directed to patent-eligible subject matter.

In summary, using conventional hardware, such as a scanner, in a conventional manner in method claim is not sufficient to make a claim patent-eligible. In addition, the Bilski “machine or transformation” test is dead and should not be relied upon.