This case concerned an appeal from a district court case which held that Visual Memory’s U.S. Patent No. 5.953,740 was drawn to patent-ineligible subject matter.

This case concerned an appeal from a district court case which held that Visual Memory’s U.S. Patent No. 5.953,740 was drawn to patent-ineligible subject matter.

The patent teaches that computer systems frequently use a three-tiered memory hierarchy to enhance performance. The three tiers include: 1) a low-cost, low speed memory, such as a magnetic disk, for bulk storage of data; 2) a medium-speed memory that serves as the main memory; and 3) an expensive, high-speed memory that acts as a processor cache memory. Because the cache memory is the most expensive, it is typically smaller than the main memory and cannot always store all the data required by the processor. The memory hierarchy alleviates the limitations imposed by the cache’s size because it allows code and non-code data to be transferred from the main memory to the cache during operation to ensure that the currently executing program has quick access to the required data. Replacement algorithms determine which data should be transferred from the main memory to the cache and which data in the cache should be replaced. As a result, the code and non-code data to be executed by the processor are continually grouped into the cache, thereby facilitating rapid access for the currently executing program. These prior art memory systems lacked versatility because they were designed and optimized based on the specific type of processor selected for use in that system. Designing a different memory system for every processor type is expensive.

The patent purports to overcome these deficiencies by creating a memory system with programmable operational characteristics that can be tailored for use with multiple different processors without the accompanying reduction in performance. It discloses a main memory and three separate caches: an internal cache, a pre-fetch cache, and a write buffer cache.

The three caches possess programmable operational characteristics that are programmable based on the type of processor connected to the memory system. When the system is turned on, information about the type of processor is used to self-configure the programmable operational characteristics. For example, depending on the type of processor, the internal cache can store both code and noncode data, or it can store only code data. Similarly, write buffer cache 20 can be programmed to buffer data “solely from a bus master other than the system processor,” or to buffer data writes by any bus master including the system processor. By separating the functionality for the caches and defining those functions based on the type of processor, the patented system can allegedly achieve or exceed the performance of a system utilizing a cache many times larger than the cumulative size of the subject caches. Using a programmable operational characteristic based on the processor type can also improve the main memory.

Claim 1 recites:

1. A computer memory system connectable to a processor and having one or more programmable operational characteristics, said characteristics being defined through configuration by said computer based on the type of said processor, wherein said system is connectable to said processor by a bus, said system comprising:

a main memory connected to said bus; and

a cache connected to said bus; wherein a programmable operational characteristic

of said system determines a type of data stored by said cache.

Under step one of the Alice test, the district court had concluded that the claims were directed to the “abstract idea of categorical data storage,” which humans have practiced for many years. The court’s step-two analysis found no inventive concept because the claimed computer components—a main memory, cache, bus, and processor—were generic and conventional.

The Federal Circuit noted that two recent cases inform their evaluation of whether the claims are directed to an abstract idea: Enfish and Thales (described in other posts in this blog). In Enfish, the Federal Circuit held claims reciting a self-referential table for a computer database were patent-eligible under Alice step one because the claims were directed to an improvement in the

computer’s functionality. In Thales, the Federal Circuit determined that claims reciting a unique configuration of inertial sensors and the use of a mathematical equation for calculating the location and orientation of an object relative to a moving platform were patent-eligible under Alice step one.

The Federal Circuit’s review of the claims at hand demonstrated that they are directed to an improved computer memory system, not to the abstract idea of categorical data storage. None of the claims recite all types and all forms of categorical data storage.

As with Enfish’s self-referential table and the motion tracking system in Thales, the claims here are directed to a technological improvement: an enhanced computer memory system. Therefore, the claims are patent-eligible.

The dissent contended that the claimed programmable operational characteristic is nothing more than a black box, and that the patent lacks any details about how the invention’s purpose] is achieved. The majority noted some flaws with this conclusion. First, the patent included a microfiche appendix having 263 frames of computer code. The dissent argued that this code would not teach one of ordinary skill in the art the innovative programming effort. The majority stated that such an assumption is improper when reviewing a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim. Second, whether a patent specification teaches an ordinarily skilled artisan how to implement the claimed invention presents an enablement issue under 35 U.S.C. § 112, not an eligibility issue under § 101. Third, the dissent assumed that the “innovative” effort in the patent lies in the programming required for a computer to configure a programmable operational characteristic of a cache memory. This assumption is inconsistent with the patent specification itself. The specification makes clear that the inventors viewed their innovation as the creation of “a memory system which is efficiently operable with different types of host processors, and the patent discloses how to implement such a memory system.

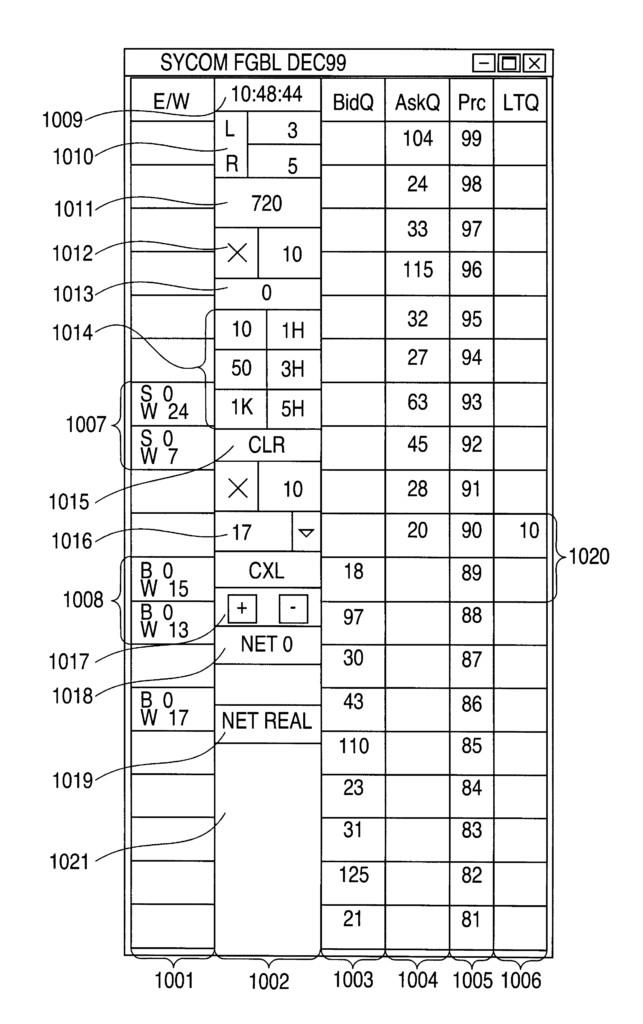

This decision should be very interesting to software developers who want software patents on unique graphical user interfaces. The decision is non-precedential, but can be cited to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office when the facts in a patent application uniquely match those in this case. Up until this case, and after Alice, the Federal Circuit had consistently found the claims to user interfaces patent-ineligible, reasoning that generically claimed user interfaces that merely present information that had been collected and analyzed are ineligible.

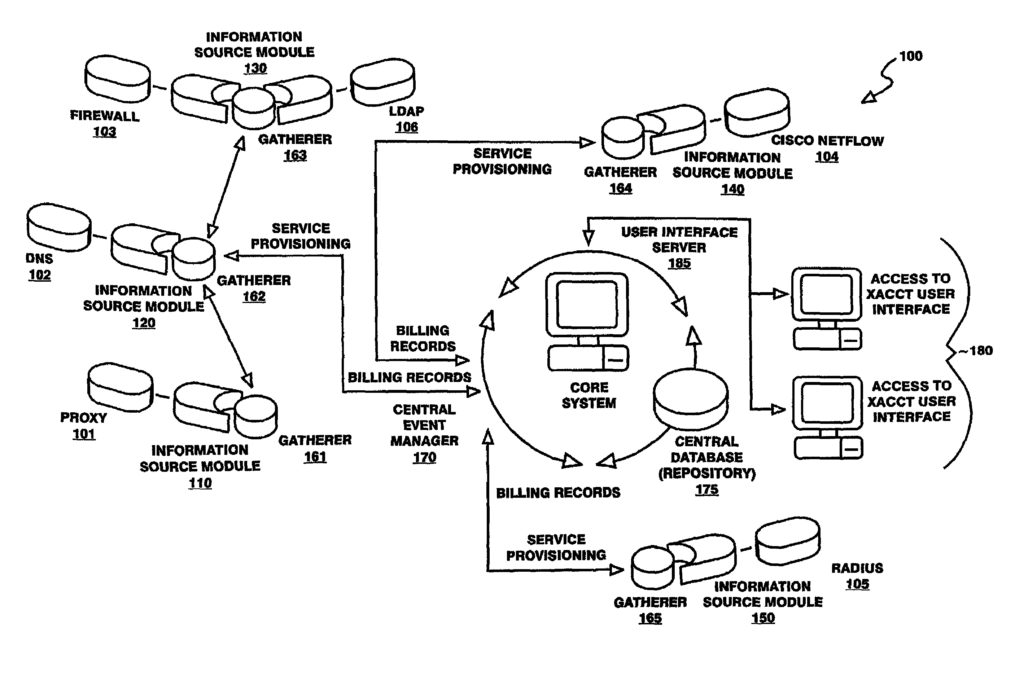

This decision should be very interesting to software developers who want software patents on unique graphical user interfaces. The decision is non-precedential, but can be cited to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office when the facts in a patent application uniquely match those in this case. Up until this case, and after Alice, the Federal Circuit had consistently found the claims to user interfaces patent-ineligible, reasoning that generically claimed user interfaces that merely present information that had been collected and analyzed are ineligible. Amdoc sued Openet over four software patents directed to solving accounting and billing problems faced by network service providers. The district court held that the software patents were directed to patent-ineligible abstract ideas.

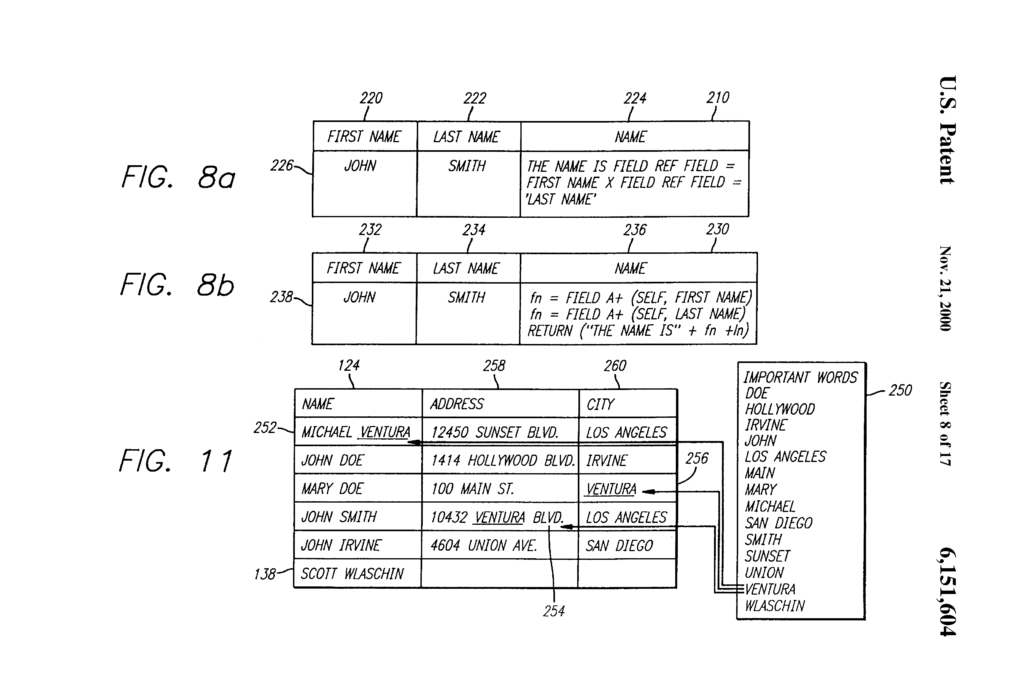

Amdoc sued Openet over four software patents directed to solving accounting and billing problems faced by network service providers. The district court held that the software patents were directed to patent-ineligible abstract ideas. Enfish sued Microsoft for infringement of U.S. Patent 6,151,604 and U.S. Patent 6,163,775 related to a logical model for a computer database. A logical model is a model of data for a computer database explaining how the various elements of information are related to one another. A logical model generally results in the creation of particular tables of data, but it does not describe how the bits and bytes of those tables are arranged in physical memory devices. Contrary to conventional logical models, the patented logical model includes all data entities in a single table, with column definitions provided by rows in that same table. The patents describe this as a “self-referential” property of the database.

Enfish sued Microsoft for infringement of U.S. Patent 6,151,604 and U.S. Patent 6,163,775 related to a logical model for a computer database. A logical model is a model of data for a computer database explaining how the various elements of information are related to one another. A logical model generally results in the creation of particular tables of data, but it does not describe how the bits and bytes of those tables are arranged in physical memory devices. Contrary to conventional logical models, the patented logical model includes all data entities in a single table, with column definitions provided by rows in that same table. The patents describe this as a “self-referential” property of the database.