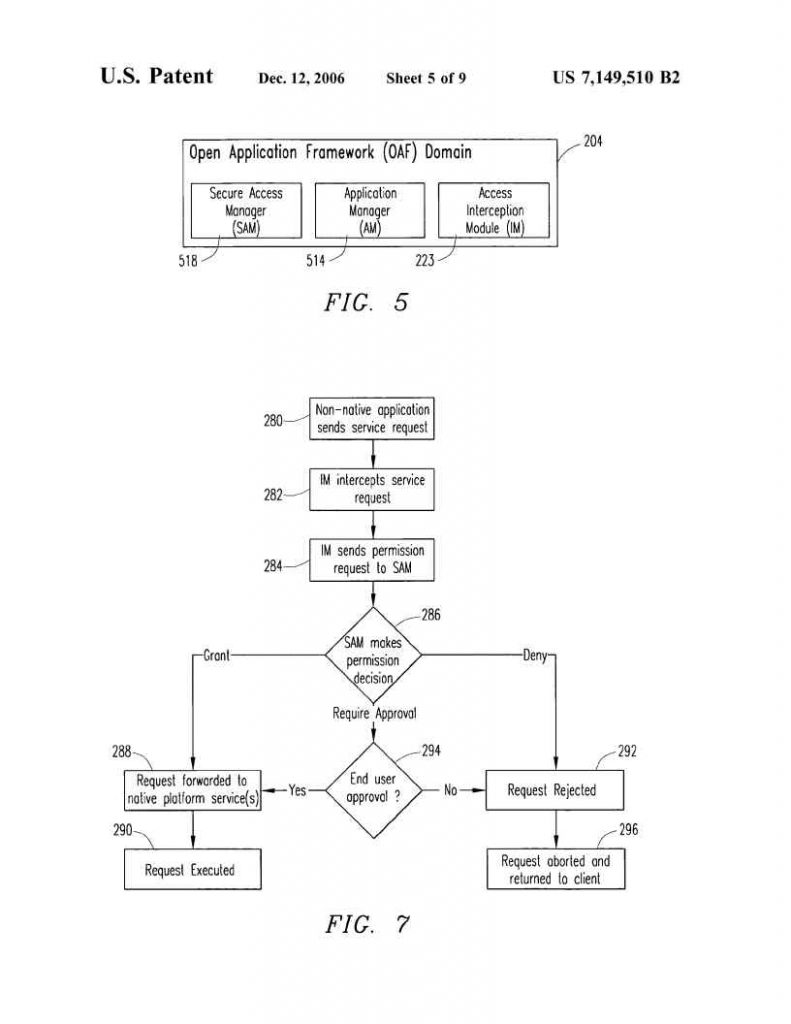

This case involves U.S. Patent No. 7,149,510 relating to securing mobile phones against improper access by apps.

This case involves U.S. Patent No. 7,149,510 relating to securing mobile phones against improper access by apps.

Claim 1 recites:

1. A system for controlling access to a platform, the system comprising:

- a platform having a software services component and an interface component, the interface component having at least one interface for providing access to the software services component for enabling application domain software to be installed, loaded, and run in the platform;

- an access controller for controlling access to the software services component by a requesting application domain software via the at least one interface, the access controller comprising:

- an interception module for receiving a request from the requesting application domain software to access the software services component;

- and a decision entity for determining if the request should be granted wherein the decision entity is a security access manager, the security access manager holding access and permission policies; and

- wherein the requesting application domain software is granted access to the software services component via the at least one interface if the request is granted.

The Federal Circuit concluded that claim 1 is directed to the abstract idea of controlling access to, or limiting permission to, resources. Although written in technical jargon, a close analysis of the claims reveals that they require nothing more than this abstract idea. By the plain language of claim 1, the “security access manager” and the “decision entity” are the same thing. According to the specification, this combined decision entity/security access manager can further be the same as the “interception module.” Because the security access manager/decision entity/interception module is the only claimed component of the “access controller,” all four components collapse into simply “an access controller for controlling access” by “receiving a request” and then “determining if the request should be granted.” That bare abstract idea, controlling access to resources by receiving a request and determining if the request for access should be granted, is at the core of claim 1.

Neither of the remaining limitations altered the Federal Circuit’s conclusion that claim 1 is directed to the abstract idea of controlling access to resources. The first limitation recites “a platform having a software services component and an interface component,” for the ultimate goal of “enabling application domain software to be installed, loaded, and run in the platform.” ‘510 patent claim 1. This recitation of functional computer components does not specify how the claim “control[s] access to a platform,” nor does it direct the claim to anything other than that abstract idea. It merely provides standard components that are put to use via the “access controller” limitation. Similarly, the “wherein” limitation simply recites the necessary outcome of the abstract idea, “grant[ing] access … if the request is granted.”

The Federal Circuit, referring to Enfish, stated that the step one inquiry looks to the claim’s “character as a whole” rather than evaluating each claim limitation in a vacuum.

Ericsson made two arguments as to why the asserted claims are not directed to an abstract idea at Alice step one. Neither is persuasive. First, it argued that the idea of controlling access to resources is not an abstract idea because it does not resemble one previously recognized by the Supreme Court.

This argument was dismissed by the Federal Circuit. Controlling access to resources is exactly the sort of process that “can be performed in the human mind, or by a human using a pen and paper,” which the Federal Circuit has repeatedly found unpatentable.

Second, Ericsson contended that its claims are not directed to an abstract idea because they “solve the specific computer problem … of controlling app access in resource-constrained mobile phones.”

The Federal Circuit disagreed. As an initial matter, the district court was incorrect to conclude that the claims of the ‘510 patent are limited to mobile platform technology,” and Ericsson is wrong to repeat that point.

Moreover, according to the Federal Circuit, the claims here do not have the specificity required to transform a claim from one claiming only a result to one claiming a way of achieving it.

In summary, the Federal Circuit wants to see, in the claims, greater details of how a computer problem is solved.

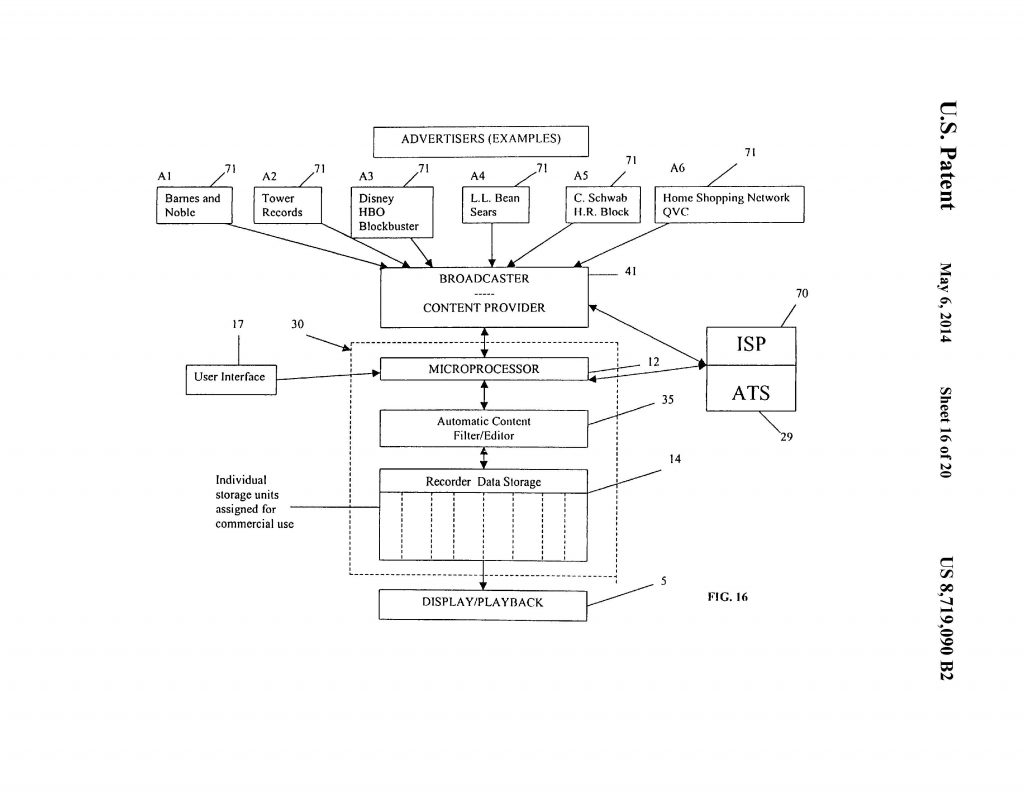

Customedia appealed a decision by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office holding claims of U.S. Patent No. 8,719,090 and 9,053,494 ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

Customedia appealed a decision by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office holding claims of U.S. Patent No. 8,719,090 and 9,053,494 ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101. Mr. Berheimer sued HP. HP moved for summary judgment that claims 1–7 and 9 of U.S. Patent No. 7,447,713 are patent ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101, and the district court granted the motion.

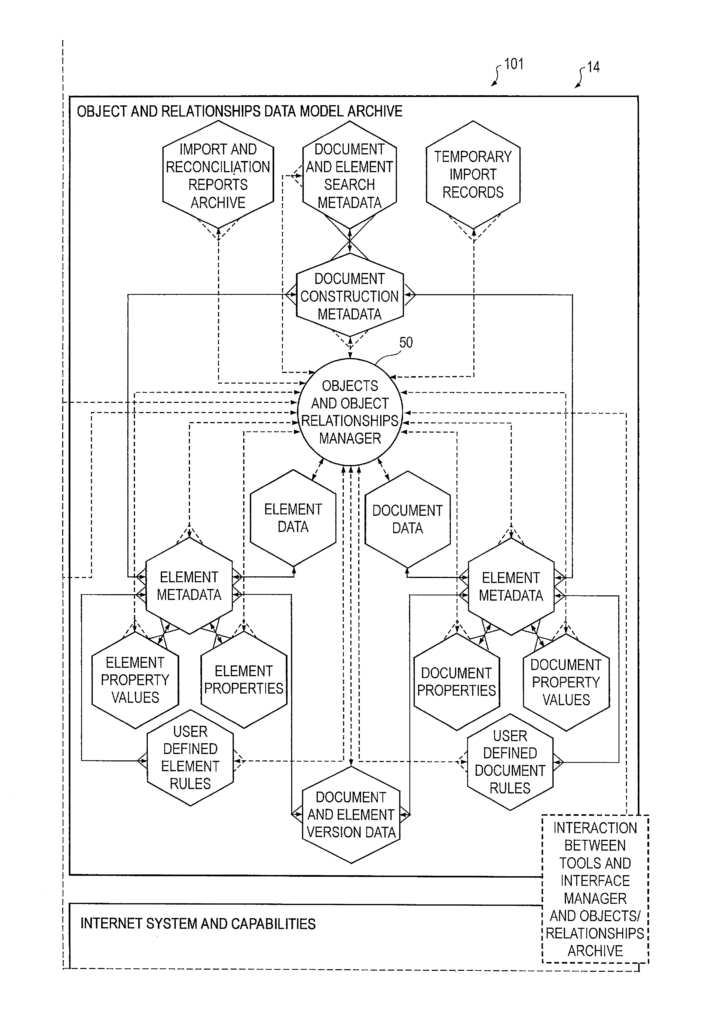

Mr. Berheimer sued HP. HP moved for summary judgment that claims 1–7 and 9 of U.S. Patent No. 7,447,713 are patent ineligible under 35 U.S.C. § 101, and the district court granted the motion. Amdoc sued Openet over four software patents directed to solving accounting and billing problems faced by network service providers. The district court held that the software patents were directed to patent-ineligible abstract ideas.

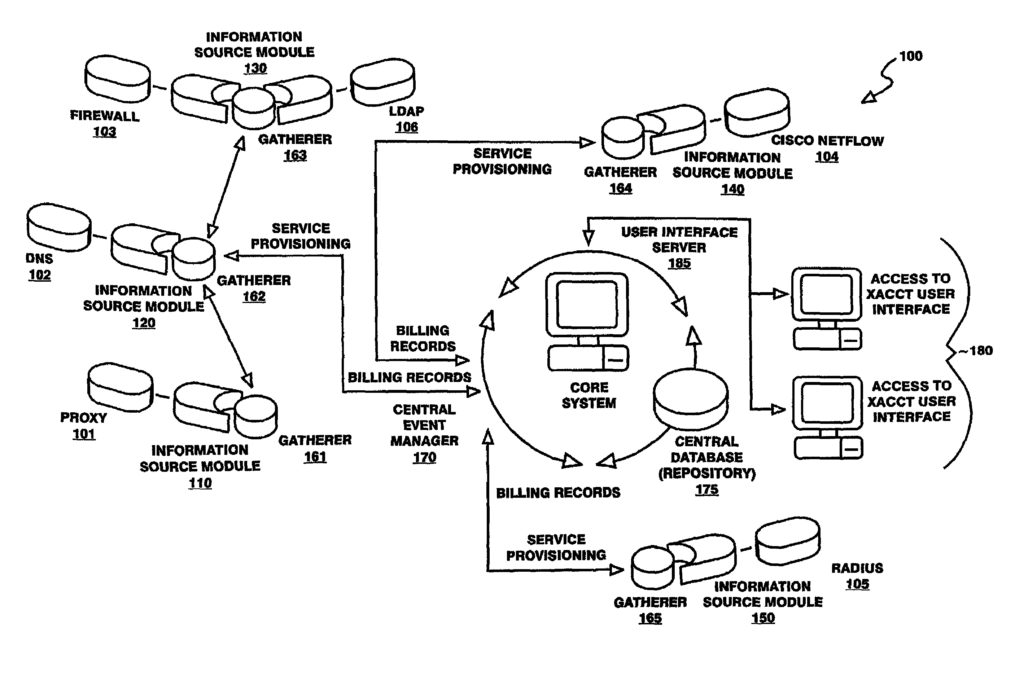

Amdoc sued Openet over four software patents directed to solving accounting and billing problems faced by network service providers. The district court held that the software patents were directed to patent-ineligible abstract ideas.